HEALTH AND SCIENCE

Recent Discoveries and Potential Breakthroughs in Microbiome Health

Lessons from Hadza hunter-gatherers about health, microbiome diversity, and holobionts

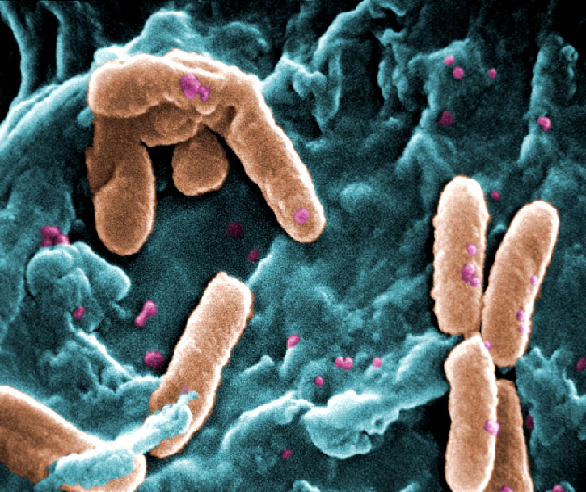

Our concept of what counts as ‘us’ has changed a lot over the last 200 years. Before we discovered microorganisms (aka microbes, microbiota or germs) in the mid-to-late 1800s, we had no idea that our world was full of microscopic life.

Fast forward to today, and we now know that good health relies on a vast network of microbes that call us home. These microorganisms, such as bacteria, are collectively known as our ‘microbiome’. And combined with our microbiome, we are known as holobionts (more on this at the end of the article).

Given the importance of microbiomes for holobionts like us, many researchers are studying how we can use this knowledge to improve our health. Today, I’ll cover some recent discoveries and potential breakthroughs in these areas and what they could teach us about staying healthy.

Hunter-gatherers have more diverse gut microbiomes

For example, one study just found that people living a modern way of life have significantly less microbiome diversity than people living as hunter-gatherers.

Research is published in journals, and this work was published in Cell, one of the three premier scientific journals in the world. (The other two elite journals are Nature and Science. Popular science podcaster and Stanford neuroscientist Andrew Huberman refers to these three as ‘apex journals’.)

The researchers worked with Hadza hunter-gatherers who live in an area of northern Tanzania. They used genetics to characterise the Hadza gut microbiome, a technique known as ‘ultra-deep metagenomic sequencing.’ They also studied people from Nepal and California and compared the results with published findings.

Almost half of the microbes identified in the Hadza gut microbiome were “unknown to existing unified data sets.” Interestingly, they found over 100 microbes that are vanishing from industrialised populations. Gut microbiome diversity was also related to microbe sharing between non-kin members, which is governed by the social structures of Hadza society.

These findings have many limitations and can never give a complete picture of the microbiome. However, these results still have considerable value, as they point towards factors that are important for proper microbiome health. Specifically, they suggest that microbiome diversity and ‘germ trading’ are important for health.

Gut microbiome diversity and health

The question then becomes, why would gut microbiome diversity benefit health? It’s impossible to say for sure right now, but we can make some guesses based on what we already know.

Genes

One possibility has to do with genes. Genes enable us to make a type of molecule known as proteins. This includes enzymes, like the ones found in our gut, which help us to break down food as it’s digested.

Needless to say, our gut microbes play a crucial role in the process, as they have their own genes and can also produce enzymes. Since proper digestion is essential for life, this means that we depend on the genes contained by our gut microbes to stay healthy.

In effect, a more diverse gut microbiome means you have a wider range of tools in your molecular toolkit. And it makes good sense to use our microbial guests in this way, as they’re an excellent source of genetic diversity.

For example, in his book Half-Earth, the late evolutionary biologist Ed Wilson pointed out that we’re more genetically similar to potatoes than the most dissimilar bacteria are to each other. Thus, by relying on our gut microbes in digestion, we take advantage of this diversity among our gut bacteria.

Mood

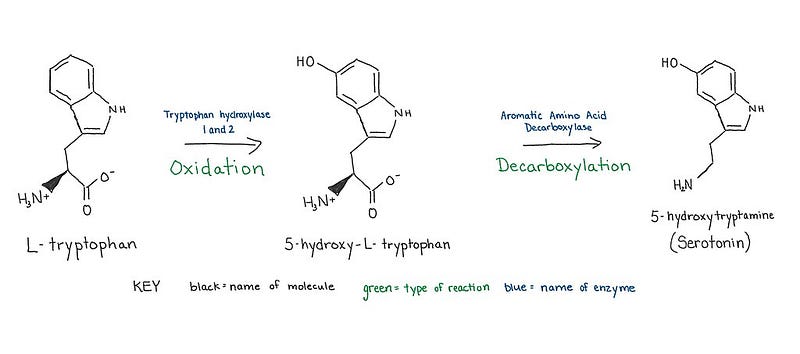

Gut bacteria also synthesise about 95% of our serotonin, the majority of which is located in our gut. Serotonin is made when an enzyme (tryptophan hydroxylase) interacts with an amino acid called tryptophan. (Amino acids are the building blocks of protein molecules.)

Serotonin is an essential metabolic regulator. It modulates our appetite, as low serotonin levels promote hunger, and high levels promote satiety. For example, this is why people who take so-called ‘party’ doses of MDMA often report loss of appetite, as MDMA increases our supply of serotonin, thus driving the feeling of being full.

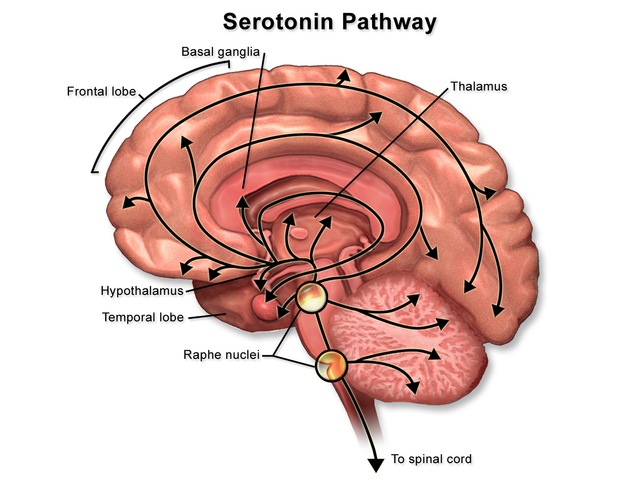

Serotonin is also a key signaling chemical in the brain. The two simplest kinds of chemical signals increase (glutamate) or decrease (GABA) the likelihood that their target brain cell will send a message to its various receivers. But serotonin belongs to a more complex class of chemical messengers that change how brain cells function instead of simply making them more or less active.

For the real keen beans, this class of signaling chemicals is known as ‘neuromodulators’, as they modulate brain cells (aka neurons). This group also includes other familiar faces, such as the famous dopamine and acetylcholine, the chemical that nicotine mimics when it affects our brain.

In the brain, the conventional story is that serotonin supports positive mood. In this view, conditions involving negative mood, like depression, are thought to indicate dysfunction in our serotonin system (e.g., not producing enough serotonin or some fault in the response to serotonin).

Given that gut microbes synthesise most of our serotonin, researchers are now studying how gut microbes affect our mood and mental health. And while it’s still very early days, many people are hopeful that we’ll find novel ways to understand and treat conditions like depression.

(At the risk of overcomplicating things, we should mention that the serotonin theory of depression has come in for major criticism lately. Researchers are still digesting this recent critique, and there’s currently no alternative to the serotonin theory of depression. Watch this space.)

The meaning of health in the age of holobionts

Important as it is for mental and bodily health, the gut microbiome is just one example of our symbiosis with microbes. Indeed, virtually every part of our bodies is host to at least a small colony of microorganisms, including our brains.

These discoveries have forced us to rethink how we understand microbes and ourselves. We no longer view all microbes as dangerous ‘germs’, as many are essential for good health. And since we can’t live without them, our resident microbes have been incorporated into a broader self-concept: holobionts.

The concept of holobionts recognises that we and our microbes are a team and that we are constantly shedding and acquiring microbes throughout our life. This is a paradigm shift in the way we see health and life, and it’s generating a lot of excitement, as was recently discussed by an article in The Economist.

The hype is more than just optimism, as current evidence implicates microbiome health in a wide range of conditions, including poorly understood conditions like autism. However, these links are all tentative for now; much remains to be learned, and no one has all the answers.

Nevertheless, we can take some general lessons from what we’ve learned. Health requires a robust microbiome, and a strong microbiome requires diversity. To be healthy, we must be exposed to the right microbes and avoid the wrong ones.

We’ve gotten better at avoiding bad microbes but have sometimes gone too far and divorced ourselves from nature. This also takes us away from the microbes we need and can cause dysfunction in the immune system, an idea known as the hygiene hypothesis.

Conclusions

Fortunately, to avoid this problem, we just need to spend time doing normal stuff outside, as we humans have done for the vast majority of our history as a species. Being in nature is good for health, and we each have to maintain our relationship with it.

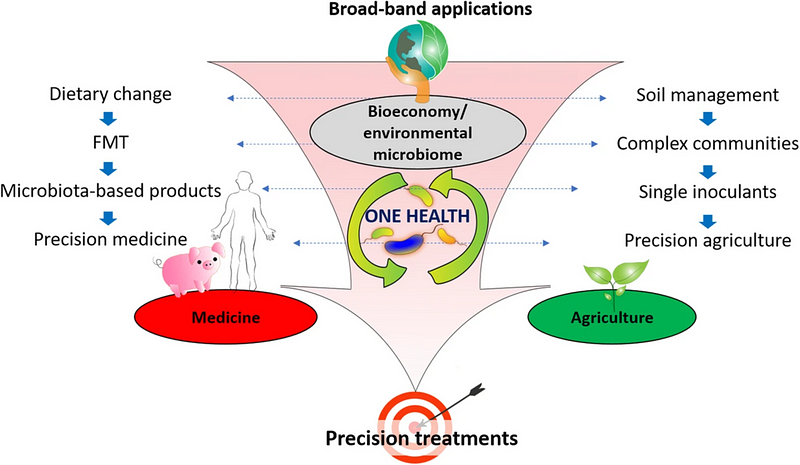

Beyond that, however, too little is currently known about most of our microbiomes to give any specific advice – except when it comes to the gut. The gut microbiome is being intensely studied, and new discoveries are being made all the time.

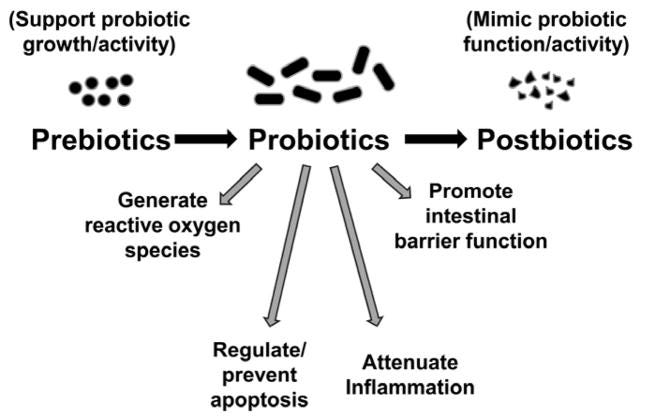

At present, there’s growing evidence to support the idea that simple strategies like exercise, different diets, and probiotics can all benefit gut microbiome health. More jarringly, even bizarre stuff like fecal transplants (yes, you read that right) are being used to share healthy microbes in order to treat various conditions. It’s a brave (and fairly gross) new world.

Nothing is certain just yet, but if you think that the health of your gut microbiome could be improved, see your doctor about what you can do.

Thanks for reading!