SCIENCE, HISTORY AND HEALTH

How Discovering Microbes Transformed Our Understanding of Life and Health

From spontaneous generation and the four ‘humours’ of Hippocrates to Louis Pasteur and modern germ theory

How does life begin, and how is health maintained? We only recently began to discover scientific answers to these questions, and our knowledge is still far from complete.

So, we’re fairly ignorant even today; how did pre-scientific people view the origins of life and the basis of health? For thousands of years, people in the West believed in an idea called spontaneous generation and the theory of four ‘humours’.

Like many aspects of the modern West, these theories of life and health trace back to ancient Greece. The relevant history occurred in the period of Classical Antiquity, which stretched from the 8th century BC to the 5th century AD.

Life, spontaneous generation, and the Ancient Greeks

In ancient Greece, conventional views on the nature of life were different from our modern understanding. Obviously, it was well known that heterosexual sex can result in pregnancy and childbirth. However it was widely believed that simpler forms of life simply sprang into existence from non-living matter.

This idea was known as spontaneous generation, and major figures like Aristotle championed it. The concept seems wild by modern standards, but its advocates had arguments that were difficult to disprove before discovering microbes.

For example, ancient people noticed how maggots would appear inside rotting meat. Since a dead animal could hardly give birth to insects, people reasoned that the dead animal’s body must provide raw material for maggots to spontaneously generate. Ancient people also applied this reasoning to other cases, suggesting that dust created fleas, and that bread/wheat left in corners gave rise to mice.

Of course, it goes without saying that mating was another obvious way that life is created. But when met with the apparently sudden appearance of organisms like maggots, fleas, and mice, the idea that simple forms of life could spontaneously generate seemed reasonable. Indeed, given that evolution wasn’t an accepted idea until well into the 20th century, spontaneous generation seemed entirely plausible for millennia.

Health, Hippocrates, Galen, and the four ‘humours’

Ancient ideas about the basis of health were also very different from our own. For around 2,000 years prior to the mid-to-late 1800s, it was received wisdom that health depended on a balance of four substances found in the body. Confusingly known as ‘humours’ (Latin for liquid or fluid), these substances were blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile.

(Yellow bile will be familiar to anyone with a severe hangover. It is released by the liver when we eat fat and helps digestion by turning fat into fatty acids. Black bile, on the other hand, was purely hypothetical and does not actually exist. More on this in a moment.)

The idea of humours had been kicked around by various thinkers for some time. But history credits an ancient Greek named Hippocrates as the first person to apply this notion to health (i.e., ‘Humourism’).

In Hippocrates’ view, the humours each had their own unique properties, and each was associated with a different season. As such, he reasoned that doctors could tell whether the humours were in balance by examining a person’s overall health, appearance, and disposition, taking the season and recent weather into account.

Empedocles, a contemporary of Hippocrates, theorised that everything was made up of the four ‘elements’: earth, fire, water, and air. Hippocrates also built this idea into his theory of Humourism, which identified each humour with a different element.

In Humourism, blood was hot and wet, and was associated with air and spring. Yellow bile (aka ‘choler’) was hot and dry, and was associated with fire and summer. Black bile (aka ‘melancholia’) was cold and dry, and was associated with earth and autumn. And phlegm was cold and wet, and was associated with water and winter.

Each person was thought to have a unique balance of the humours, which gives rise to our different personalities. People with an abundance of blood (linked with spring) were described as sanguine, meaning positive and optimistic. Personalities driven by yellow bile (i.e., choler, linked with summer) were described as choleric, meaning quarrelsome, angry, and ‘hot-tempered’.

A temperament driven by black bile (i.e., melancholia, linked with autumn) was called melancholic, meaning you’re predisposed to being introspective and sentimental. In centuries to come, melancholy/melancholia became bywords for quiet sadness and were forerunners to our modern concept of depression. Lastly, phlegmatic personalities (linked with winter) were thought of as passive, calm, and unemotional.

Hippocrates was a giant of ancient medicine. Even today, he’s widely known as the father of medicine, and his mantra about the responsibilities of doctors remains in use (i.e., the Hippocratic oath). Adding further to the clout of Humourism, it was also championed by another major figure in the history of Western medicine: Galen.

Galen was also a titan of ancient medicine, being the personal doctor to four Roman emperors in the 2nd century AD. Galen’s work across many branches of medicine and biology framed much of Western medical science for well over a thousand years, and Humourism took a central role in Galenic philosophy.

For example, this influence was on full display in the popular literature of medieval Europe, including the work of William Shakespeare. Take Hamlet, who complains of a melancholic disposition after his dad dies and his mum soon marries his uncle (honestly, fair enough, Hamlet). Shakespeare also explored melancholy with many other tragic characters, such as King Lear.

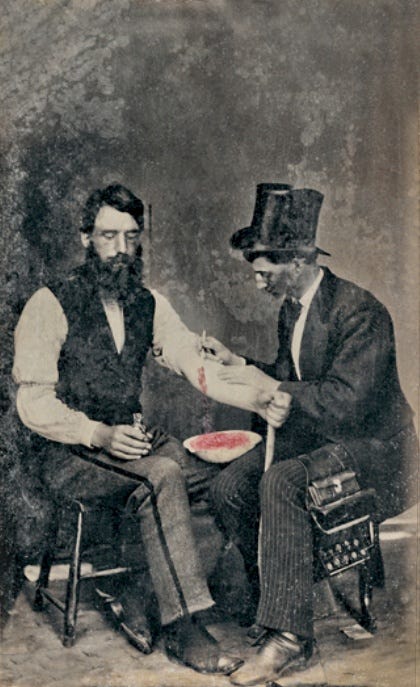

The infamous practice of blood-letting also emerged directly out of Humourism. The idea was that a person had too much blood, which a doctor would diagnose when someone presented with conditions involving loss of blood (e.g., nose bleeds and dysentery). This was interpreted as indicating a surplus of blood, so the obvious solution was to remove the excess blood.

Louis Pasteur, the birth of germ theory, and the demise of ancient beliefs

Humourism and the concept of spontaneous generation remained orthodoxy for over 2,000 years. Indeed, Galen and Hippocrates were held in such high regard that it was widely considered heresy to even question their wisdom. A person looking for answers would often be told, “you’ll find it in Galen.”

However, some rebels noticed shortcomings in the theories of the ancients and came up with new theories to replace them. Perhaps the most successful example of this was the 19th-century scientist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), known to history as the father of germ theory, immunology, and vaccinology.

Pasteur vs spontaneous generation

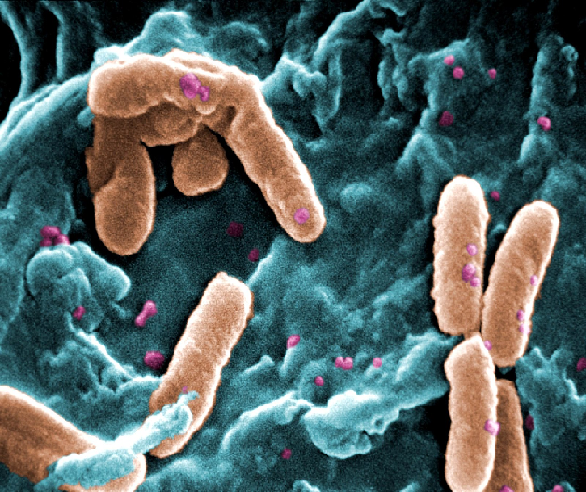

Pasteur showed that beverages, such as beer, wine, and milk, spoil not because of spontaneous generation but because of microbes (aka microorganisms, microbiota or germs). He also developed a method to kill the microbes using heat, a process known today as pasteurisation.

With these discoveries, Pasteur demonstrated the existence of microbial life, and confirmed that microbes can interact with non-living matter (e.g., proliferating by consuming sugars in drinks, thus spoiling the beverage). These experiments were crucial to disproving the idea of spontaneous generation, as Pasteur himself boldly declared to a meeting of scientists in France:

Never will the doctrine of spontaneous generation recover from the mortal blow of this simple experiment. There is no known circumstance in which it can be confirmed that microscopic beings came into the world without germs, without parents similar to themselves.

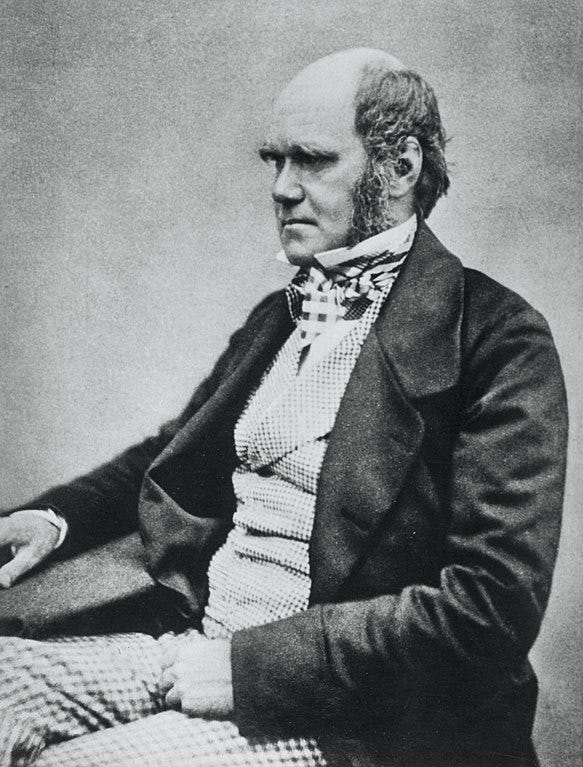

Around the same time, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) also proposed his theory of evolution by natural selection (i.e., the organisms most able to adapt are most likely to survive and reproduce). This provided a unifying framework for the study of life (i.e., biology), and was another nail in the coffin for the concept of spontaneous generation.

Pasteur vs Humourism

Pasteur then demonstrated that certain microbes are associated with various diseases and that we can treat those diseases if we understand the microbes that cause them (usually called ‘germs’). For example, in an attempt to help farmers, he studied the bacterium that causes cholera in chickens (and also affects humans), later named Pasteurella multocida after Pasteur.

Thanks to a chance mistake by one of Pasteur’s colleagues (who forgot to finish his work before going on holiday), they discovered a method to reduce the virulence of the bacterium. They then found that exposing chickens to the less-virulent strain of the bacterium provided protection against more-virulent strains, thus providing a way to prevent chicken cholera.

With these studies, Pasteur and his team created the first ever vaccine (though one intended for chickens). They followed this up with a vaccine for a disease in pigs, and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Through this work, Pasteur created the twin fields of vaccinology and immunology. And just as his earlier research disproved spontaneous generation, Pasteur’s work on the germ theory of health discredited the idea of Humourism.

It’s truly remarkable that one person was so pivotal in toppling two well-entrenched ideas, and reshaping our understanding of life, health, and disease. Although, like habits, old doctrines die hard, and Humourism took its time falling into the dustbin of history.

As an example, suppose you could go back to Sydney, Australia in the year 1900. This is decades after Pasteur’s discoveries and five years after he was buried in a state funeral for his scientific services to humankind. What would you find? Alarmingly, many doctors were still treating patients based on the now long-discredited tenets of Humourism — yikes!

Modern views and lingering questions about life and health

Our understanding of life and health has come a long way from the days of spontaneous generation and Humourism, and yet we still have much to learn. Even today, we cling to various doctrines that seemed intuitive in their heyday but are currently being challenged.

In the Western world (aka WEIRD world), one such doctrine is our strong emphasis on the individual and general neglect of group-level dynamics. The spirit of this idea was captured well by the Iron Lady, former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who stated in 1987 that “there is no such thing as society! There are individual men and women, and there are families.”

In research, this focus on the individual is called methodological individualism. In effect, researchers assume that we can fully understand humans by studying them as individuals.

From this point of view, the basis of health and disease is to be found inside individual people. For example, you’re depressed? You must have a faulty part, so let’s look inside your brain and body to find the dysfunctional component.

But this approach neglects the fact that we’re an obligate social species, meaning that we need each other in order to survive and thrive. Many books with catchy titles have recently been published on this topic, like The Social Instinct by evolutionary biologist and behavioural scientist Nichola Raihani.

A long-running study by researchers at Harvard also makes a similar point. They have studied happiness for around 80 years and have identified the primary factor that predicts a happy life. The results? Having positive and meaningful relationships, just as you’d expect for highly social animals such as ourselves.

Of course, we need to understand people as both individuals and groups, and there are many individual and social factors that determine health and happiness. For example, can we easily maintain positive and meaningful relationships if we’re chronically ill with a congenital disease, living in poverty, and/or homeless?

But we can’t let our Western (aka WEIRD) bias for individuals blind us to the importance of groups and social life, or we’ll run down many blind alleys in our search for health.

On a related note, to learn about how recent discoveries are also challenging our intuitions about energy, weight loss, metabolism, and health, check out my other article here.