HEALTH AND SCIENCE

Which Type of Intermittent Fasting is Best for Weight Loss and Health?

Comparing total and substantial daily calorie restriction with religious fasts and time-restricted eating

Fasting is an ancient practice with many potential benefits for managing weight and health. It has been used in many contexts for centuries, perhaps most famously in the yearly Islamic period of Ramadan.

In particular, intermittent fasting is currently taking the world by storm. Its virtues have been discussed in books, articles, TV segments, and published research papers, and the buzz around intermittent fasting has raised hopes that we can ease the global crises in health and obesity.

As we discussed in a recent article, this is because studies using doubly-labeled water have shown that weight loss requires calorie restriction, as we burn the same amount of daily calories no matter how much we exercise. As a result, people are turning to strategies like intermittent fasting as a tool to restrict calories and combat obesity and related conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

But intermittent fasting comes in many shapes and sizes, so we need to know which approaches produce the greatest benefits. Fortunately, this question has been addressed by research in recent years, as we’ll discuss today. We’ll look at the major types of intermittent fasting and briefly summarise what we know about their benefits.

As we’ll see, there are mixed results for strategies that use days of total or substantial calorie restriction, like the 5:2 diet, and for the benefits of religious fasting, such as Ramadan. In contrast, time-restricted eating seems to be the most beneficial, especially when limited to daylight hours.

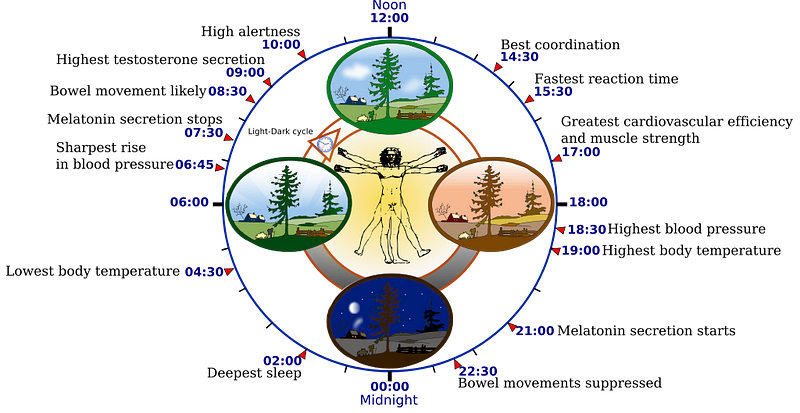

I’ll link these findings to what we know about the roles of hormones like insulin; how circadian rhythms influence our health and weight; and outline how you can experiment with intermittent fasting.

Comparing different types of intermittent fasting

1 — Days of total or substantial calorie restriction

One type of intermittent fasting involves eating no food on a certain number of days per week. In another version of this approach, people are restricted to 20–25% of their normal daily calorie intake on those days.

In research jargon, the total calorie restriction approach is known as ‘alternate-day fasting’, while the substantial calorie restriction approach is often called ‘modified fasting’.

One popular example of these approaches is the 5:2 diet.

Studies on alternate-day fasting (days of total calorie restriction) have shown that it can produce modest weight loss. Some studies also found that alternate-day fasting can lead to improvements in various measures of metabolic health in overweight people, like reduced levels of sugar, fat, and cholesterol in the blood.

Unfortunately, other studies did not replicate these benefits, producing very mixed results. In fact, some even found negative effects of alternate-day fasting on measures of blood sugar and insulin. Many people also found this regimen unpleasant, reporting intense hunger, worse mood, and impaired work performance during days of fasting.

What about days of substantial calorie restriction?

Sadly, these ‘modified fasting regimens’ don’t fare much better, as studies indicate only modest weight loss and provide mixed results from bioregulatory markers of metabolism and health.

However, the news isn’t all bad for modified fasting regimens.

For example, people report that days of substantial calorie restriction are more tolerable than days of total fasting and can lead to improvements in mood, stress, anger, fatigue, and self-confidence.

2 — Religious fasting

The most well-known and widely-practised period of time-restricted eating occurs in the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. Muslims abstain from all food and drinks during daylight hours and break their fast before dawn and after sunset.

Studies indicate that Ramadan results in modest weight loss of around 1kg, which most people promptly regain in the following weeks. Given that Ramadan is a religious event, not a weight-loss strategy, this makes sense.

Still, there is some evidence that daytime fasting during Ramadan may improve some aspects of health. For example, one study suggested that it may improve the body’s regulation of blood sugar in people with type 2 diabetes.

Other studies (e.g., here and here) suggest that fasting during Ramadan may also reduce cellular inflammation, a risk factor for many serious and life-threatening diseases (e.g., cancer).

However, the overall evidence is mixed, and systematic reviews do not show a clear benefit to biomarkers of metabolism and/or health.

Fasting during daylight hours is also contrary to our normal circadian rhythm (more on this later) and would not be a convenient weight-loss strategy for most people.

By contrast, some Christian denominations adopt types of time-restricted intermittent fasting that seem to offer many practical lessons.

For example, one study found that Mormons who practice routine fasting were thinner, had lower levels of blood sugar, and were less likely to have diabetes and certain cardiovascular diseases.

Seventh-Day Adventists are also very instructive, as they promote healthy living as part of their faith. They advocate not smoking, getting regular exercise, eating a plant-based diet, and limiting themselves to two meals per day. What’s more, research from California suggests that Seventh-Day Adventists live about seven years longer than people from similar demographics.

Interestingly, Seventh-Day Adventists often consume the last of their two meals in the afternoon. This results in a prolonged period of fasting until the next day, most of which occurs outside of the daytime. This means that mealtimes for Seventh-Day Adventists are usually confined to daylight hours, in sync with their circadian rhythm.

3 — Time-restricted daily eating

Research in animal models (usually other mammals, like rats or mice) has long suggested that this type of time-restricted fasting regimen helps to lose weight and boost health. This is true in both males and females.

However, as with many things, timing matters. Studies in animal models show that the greatest benefits are gained when periods of eating align with normal waking hours and periods of fasting align with sleep.

Animal models even indicate that eating outside of daylight hours may contribute to obesity, chronically high insulin, and insulin resistance. (To learn more about how insulin and insulin resistance affect our health and weight, see this article by Dr Mehmet Yildiz.)

Epidemiological studies suggest that something similar occurs in people engaged in shift-work. This is because shift-work is associated with eating at night, and shift-workers are at greater risk for obesity, diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease.

Fortunately, research also indicates that time-restricted feeding limited to normal waking hours can be an effective intervention for diet-related obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Although this isn’t much use to shift-workers.

Results on time-restricted eating are not uniformly positive. For example, some studies fail to find any benefits for weight loss and health. Others suggest that time-restricted eating produces similar benefits to more conventional methods of calorie restriction, like low-calorie diets.

Nonetheless, among the major types of intermittent fasting, time-restricted eating seems to be the most promising. This is because it’s relatively convenient for people’s lives; naturally promotes healthy behaviours by aligning with our work and circadian rhythm; and improves weight loss and health for many people, especially if they’re overweight.

One popular approach is the 16:8 rule. This means you fast for 16 hours, most of which occurs overnight, and eat in an 8-hour window during the daytime. For many people, this means skipping one meal a day, like eating breakfast and lunch but not dinner or lunch and dinner but not breakfast.

There’s currently no clear evidence that skipping any particular meal is best, with different people passionately arguing over whether breakfast is essential or should be skipped. Until we know more, we simply have to reserve judgment.

In the meantime, if you want to try time-restricted eating, you should pay attention to your body and experiment until you find the right regimen for you.

Maybe you’ll flip the script and skip lunch rather than breakfast or dinner — no need to be too dogmatic when we still have so much to learn.

Conclusions and Takeaways

Contrary to our intuitions, we can’t exercise our way out of a bad diet. Studies using doubly-labeled water have shown that to lose weight, we have to ingest fewer calories than we burn.

But when we’re surrounded by the delicious, affordable, calorie-dense foods of the modern world, this is easier said than done.

One useful tool in this struggle is intermittent fasting, which has emerged as a promising way to restrict calories and lose weight. But intermittent fasting comes in a range of flavours, and studies indicate that they are not all equally effective.

Among the major types of intermittent fasting, time-restricted eating currently seems to be the best. This isn’t due to differences in weight loss, as studies suggest that all the main types of intermittent fasting produce similar reductions in calorie intake and weight.

But people report that time-restricted eating is easier to mentally and physically tolerate than days of total or near-total fasting, as is done in alternate-day and modified fasting regimens, such as the 5:2 diet.

Since time-restricted feeding is less detrimental to daily wellbeing, people are better able to function at work and are more likely to stick to their diet.

Time-restricted eating also has a range of incidental benefits. Limiting eating to daylight hours aligns our eating schedule with our circadian rhythm, borrowing from the healthy and long-living example of Seventh-Day Adventists.

Importantly, it also gives people the freedom to pick and choose which meal(s) to shrink or skip, allowing them to tailor their diet to the needs and circumstances of any given day.

For these reasons, time-restricted eating stands out as the gold standard for intermittent fasting, at least in my opinion. One popular approach is the 16:8 rule, where people fast for 16 hours (mostly overnight), and eat within an 8-hour window during daylight hours. Lots of people find some version of this strategy very helpful, and it will be a good place to start for many people looking to experiment with time-restricted eating.

We’ve been culturally conditioned to believe that hunger is bad and to be avoided, but this is far from the truth. Hunger is a normal part of life, and has been a constant companion across our evolutionary history.

This fact of life is woven tightly into our biology as we have evolved to be caloric misers — an adaptation to regular bouts of extended hunger.

But cultural conditioning can be unlearned, and if we understand the quirks and limits of our biology, we can turn weaknesses into strengths. If we each experiment until we find dieting routines that suit us as individuals and learn from each other’s experiences, we can win our battle with the bulge.

In doing so, we’ll also dramatically reduce our chances of getting seriously ill and dying from a range of conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. There’s currently no drug or medical treatment that offers such promise for improving the global crises in health and obesity.

Many are excited about this opportunity, but we also have to remember that life is a team sport, and we need to work together in order to thrive. If we embrace hunger as a tool rather than an obstacle, share our experiences, and support each other when times are tough, we have everything we need to live longer, healthier, and happier lives.

Thanks for reading!