The Optimism of the Most Famous Artist’s Bedroom in History

Uncovering the story of Van Gogh’s vibrant abode

What impels an artist to paint? What kind of urge takes them to the canvas to begin working?

I’d like to say that paintings are, amongst other things, an attempt to seize the visible world before it changes — as it is so prone to doing.

It might be a view, a ray of sunlight, an expression on a face, a certain arrangement of colours presented before the artist. Even as we move around a room our view of things is perpetually revising.

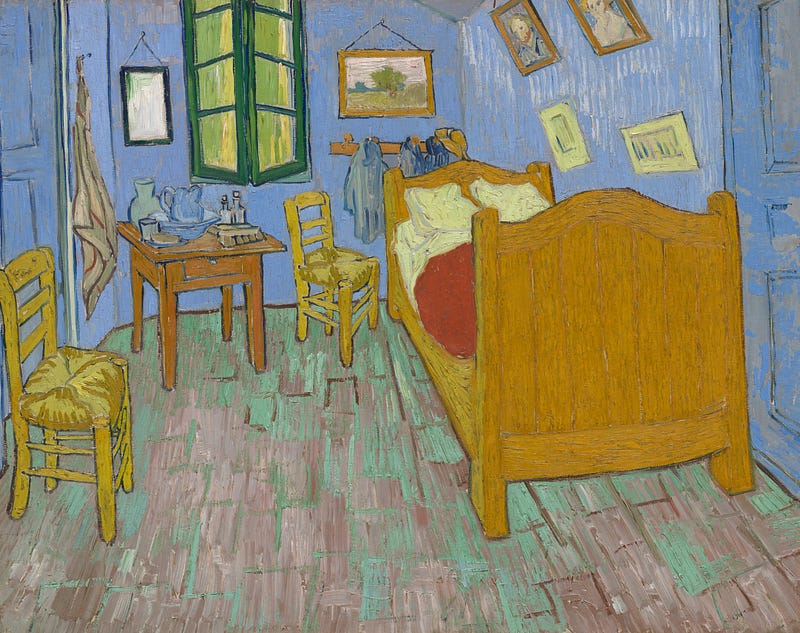

When Vincent van Gogh painted The Bedroom, his creative energies were in full flow. In various ways, the painting is an attempt to pin down these transitory moments, when the artist’s new abode was pristine and all of his hopes for the future were intact…

Finding personal freedom

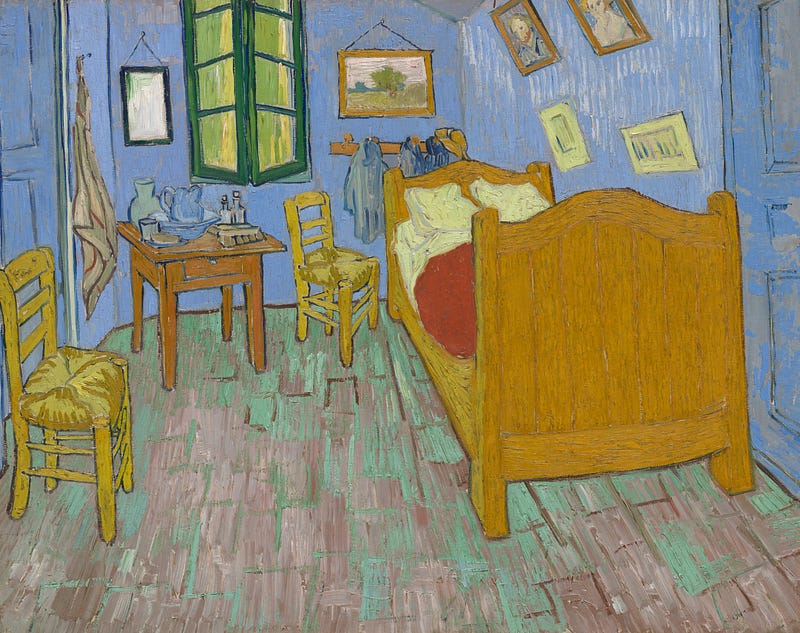

The Bedroom depicts Van Gogh’s newly rented studio home in Arles, the “Yellow House”, where he began living in September 1888.

Decorating and furnishing the house was a carefully planned effort. He was also painting new artworks at a furious rate, sometimes working up to 16 hours a day. Exhausted from both pursuits, he “rested for two and a half days”, after which he commemorated his bedroom on canvas.

To my mind, it is a painting bursting with optimism, a freshly acquired sense of liberty, and the invaluable advantage of possessing a permanent studio space to work in.

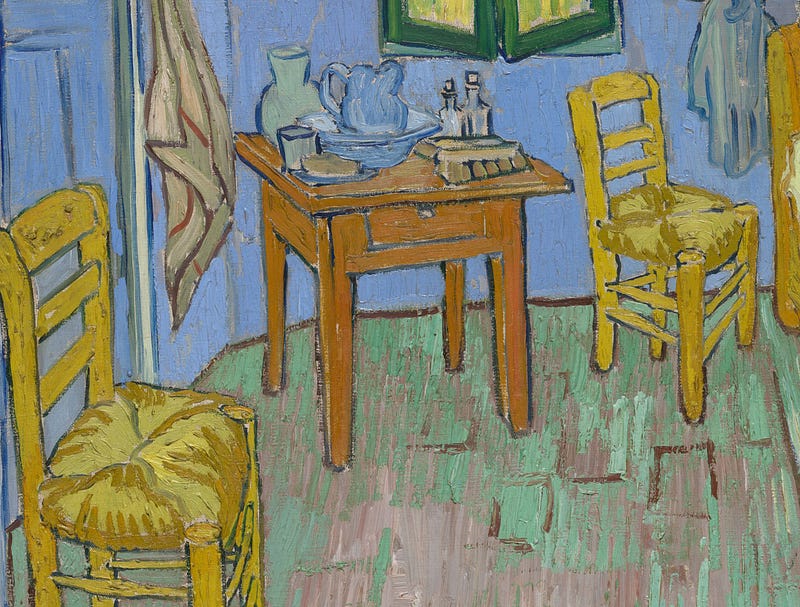

A pair of green shutters are slightly ajar, letting in the glow of daylight from the Place Lamartine. Two chairs face the open room, positioned as if ready to be sat on. One of these he would later immortalise in paint.

On the distant wall there is a mirror, recently purchased, hanging above the washstand, possibly aiding in the creation of his self-portraits during this period. And from a series of hooks hang his garments, among which is his recognisable straw hat that shielded him from the Mediterranean sun and appeared in several of his self-portraits.

The door on the left leads to the guest room that was being prepared for the arrival of the artist Paul Gauguin. One of Van Gogh’s hopes for his new house was for artists to come and stay, and work alongside him.

In this way, the room became a hub of his artistic choices and intentions.

Different versions

Van Gogh actually painted several versions of the same interior view.

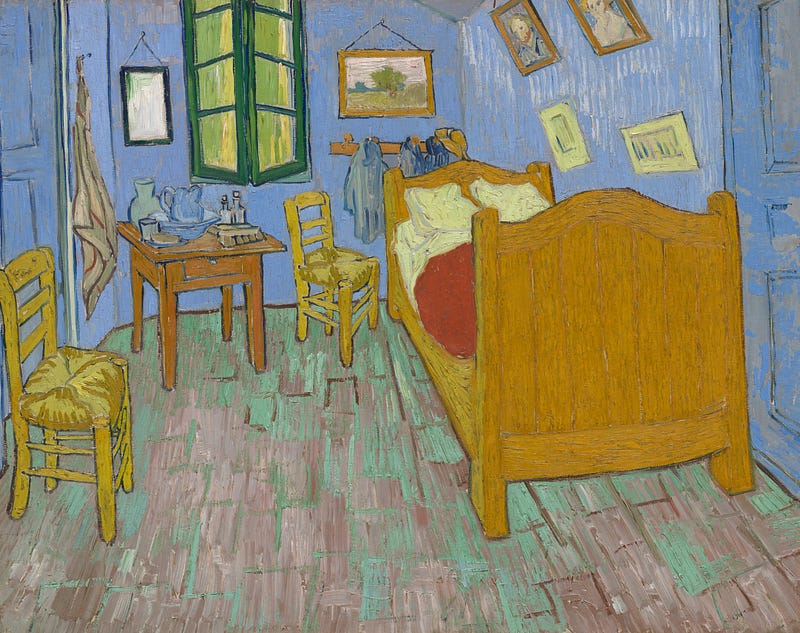

The first (above left) was made just a couple of months after moving into the Yellow House, whilst the second was made during the following spring after the original version suffered water damage.

Between the two versions, whilst almost identical on first appearance, it’s possible to trace important differences, all of which reflect a more expressive style that Van Gogh was developing at the time.

Notice in the first version how the chair is painted in mainly flat tints, whilst the later version is given a more textural finish with impasto brushmarks, most evident on the woven seat of the chair.

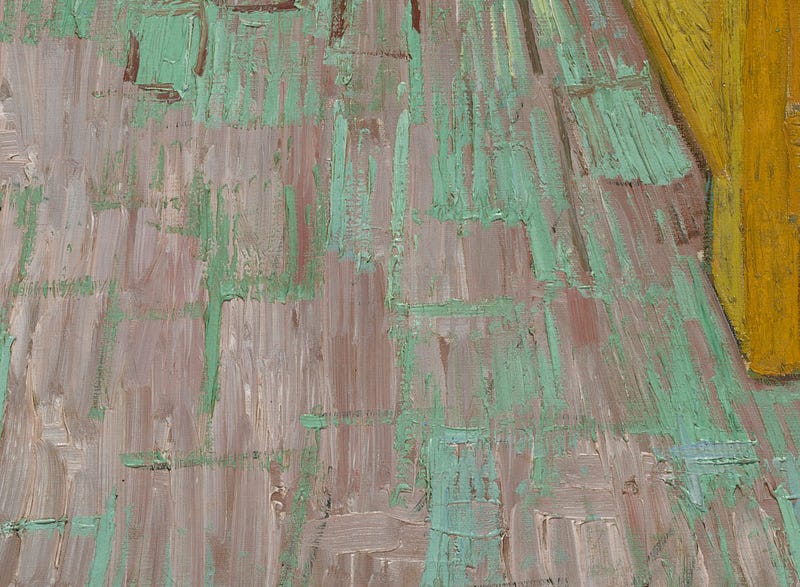

Likewise, the walls and floor are made up of several layers of paint to form the base colour and highlights on top.

Originally the walls were a “pale violet” — as described by Vincent in a letter to Theo — but deterioration in the blended red pigment has left only the blue tones that we can see today. Similarly, the floor was originally a stronger tone of red.

It’s noticeable too that the window in the first bedroom appears more flattened, whereas in the second bedroom both windows form a more pronounced pyramidal effect, bringing more life to the room.

As for the wall-hung portraits, in the initial painting Van Gogh meticulously captured the images mounted on his new bedroom wall, featuring Eugène Boch and Lieutenant Paul-Eugène Milliet.

In the later version, the two portraits have changed: they show Van Gogh himself and next to him an unknown woman — offering a hint of the domestic companion that Van Gogh always longed for.

A room on the verge

From Van Gogh’s letters, it seems the idea for the image was to express calmness, yet given the peaceful tone that he was after, it’s interesting to notice the unlikely tilt of the floor, which gives the impression that the furniture is almost about to slide towards us.

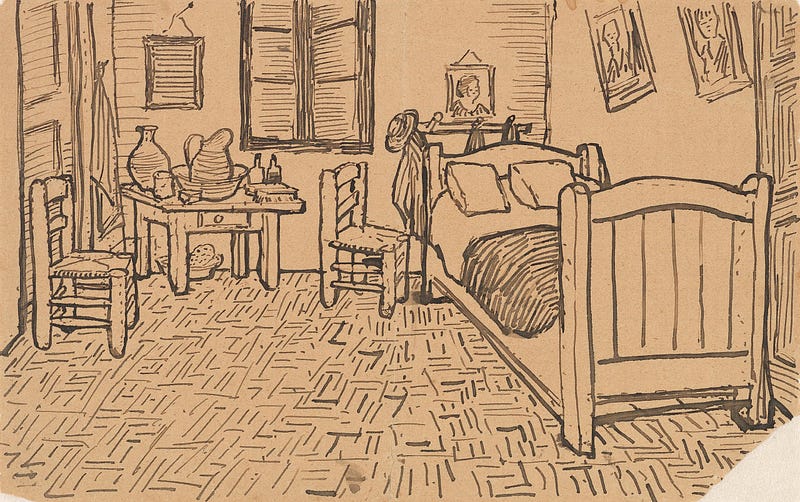

A deeper understanding of the intentional distortion can be gained from a sketch that Van Gogh enclosed in a letter to Theo. In this sketch, whilst the room’s layout is almost exactly the same, the tiled floor is much less sloping.

In the finished paintings, the room has been made narrower, achieving a more urgent sort of immediacy, and giving the sense that the whole room is on the verge of something. This perspective pitch brings each object in the room closer to the surface of the work, within touching distance as it were.

To my mind, this brink is not terrifying but charged with anticipation, expressing the threshold of a new creative existence that Van Gogh was on the cusp of.

Moreover, each item in the room is laid on the surface of the canvas like a cut-out. Look at how the chairs, bed and table have been outlined in thick brown-grey lines, emphasising their importance as individual items. These objects cast no shadows; instead they stand there, close at hand, ready to be used.

Van Gogh wrote to Theo about the style of the painting:

“The broad outlines of the furniture must express unwavering rest. [..] The shadows and cast shadows are removed; it’s coloured in flat, plain tints like Japanese prints.” (16th October, 1888)

Van Gogh’s reference to Japanese prints is notable: Japan held a magical significance for him, despite having never visited the country. In his mind, the rural simplicity of Arles was like a French version of Japan.

His impressions of Japan were largely drawn from Japanese woodcut images, of which he owned a sizeable collection, some picked up in Antwerp and others collected at Parisian boutiques. The prints gave him a window onto a culture he came to idealise, so much so that he made painted copies of several prints to learn more about their colours, composition and unique spatial effects.

Evidently, the flat tones of The Bedroom were inspired by his Japanese collection. The aim was not tonal contrasts nor depth of space but an intuitive sense of harmony. As he described to his friend Paul Gauguin in October 1888, his bedroom painting was made…

“… In flat tints, but coarsely brushed in full impasto, the walls pale lilac, the floor in a broken and faded red, the chairs and the bed chrome yellow, the pillows and the sheet very pale lemon green, the bedspread blood-red, the dressing-table orange, the washbasin blue, the window green. I had wished to express utter repose with all these very different tones.”

What happened next

October 1888 was a pivotal month in Van Gogh’s life. On the 23rd October, just a few days after he had completed his first version of The Bedroom, he welcomed Gauguin into his home. The long-awaited “Studio of the South” had come to fruition.

However, the two artists found it difficult to work together and their temperaments clashed. They quarrelled repeatedly. Before the year’s end, Van Gogh had mutilated his ear and Gauguin had fled to Paris.

Van Gogh was hospitalised after the event, during which time the original painting — along with several others — was damaged in a flood.

Despite this, on his recovery he returned to the painting of his bedroom as the most gratifying of his recent works, as he expressed to his brother on 22nd January 1889:

“When I saw my canvases again after my illness, what seemed to me the best was the bedroom.”

Given his fondness for The Bedroom, it is also understandable that he chose to remake the painting, which he did in April 1889 whilst at an asylum in Saint-Rémy. He also went on to make a third version as a gift for his mother and sister Wil, painted a few weeks later when he undertook to copy some of his most successful compositions on a smaller scale — or réductions to use Van Gogh’s term.

Together, all three versions of The Bedroom serve as a poignant commemoration of Van Gogh’s private space, a simple room full of light and — by implication — hope.

And if the painting reveals Van Gogh’s pleasure in his new autonomy and creative freedom, then the two chairs, two pillows on the bed, and two portraits on the wall, also suggest a poignant wish to share this freedom with someone else — a desire that was never to be fulfilled.

If you liked this, you may also be interested in my book Great Paintings Explained, an examination of some of the most beautiful objects in art history.

Would you like to get…

A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History? Download for free here.

Join me…

On Instagram for more great paintings on the go!