The Endless Gray of Being a Refugee, a War Victim

Being unwelcome, uncared for, and vilified in a world of violence

Gray is rarely anyone’s favorite color. If we wear it, we tend to complement it with a brilliant shade of green, blue, or red. It feels like the color of a cemetery, of death.

Gray is often ugly. The color of a dreary day, a rain-filled day, a muddy puddle, a dead tree. These are images we want to put out of our minds, forget about.

It’s hard to find photos of them, because we don’t tend to take pictures of ugly, gray times. We prefer to remember happy days and blue skies. I’m struggling to find photos for this essay, even when I change the color to black and white.

I’ve worked with refugees and war victims around the world for 22 years. As I thought about this writing challenge, my mind went immediately to those I have met in Ghana, Uganda, New Zealand, Japan, Greece, France, the US. Hundreds of humans brimming with life and the desire to live safely and freely (millions, but I have personally met and worked with hundreds). People who have endured more horrific events than most Medium writers and readers can imagine, but who hold the hope of beginning again.

Refugees do not ask for this journey from their homelands. The vast majority would stay in their homelands were it safe. They don’t ask to travel, often on foot, hundreds or thousands of miles to a new place where they don’t know the language or the customs, where they don’t know how they will find jobs or a way to provide food and shelter for their children.

I have had refugee children in the United States tell me about watching members of terrorist groups climb over walls to ransack their villages and rape and kill their family members. I’ve talked with children in Uganda who were stolen and forced to become child soldiers for the Lord’s Resistance Army. Several of the girls were forced to become “wives” to the terrorists and gave birth to children of terrorist commanders. They were not initially welcomed when they could finally return to their villages. Mothers of these stolen girls told me their stories of how they risked their lives to track down their daughters. Many endured years of sleepless nights wondering if their children were still alive.

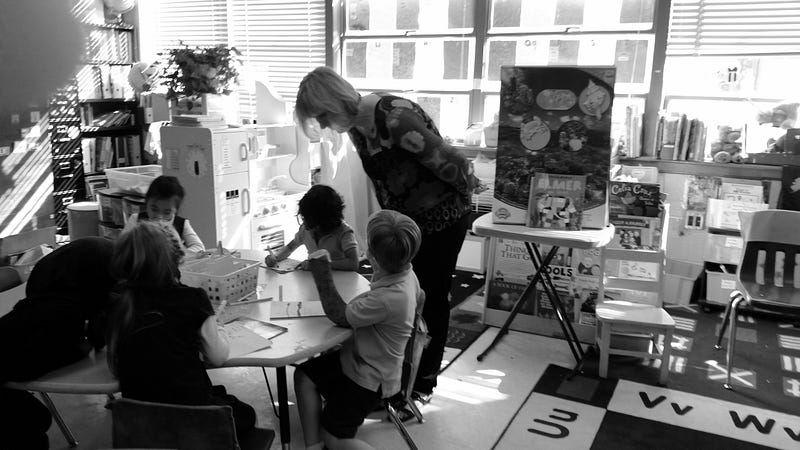

In Ghana, I met talented children in schools who I have tried to help. I’ve paid for two highly talented artists to complete their studies. I’ve introduced them to acquaintances in the US who I thought might be able to help. These two boys were forced to return to Liberia when the UN shut down the Buduburam Refugee Camp in Ghana. So talented, with no real prospects to make their talent known to the world.

In Japan, asylum seekers told me that the key was to make it through the airport. If they could do that, they could apply for asylum (which they wouldn’t get; Japan only grants asylum to a few dozen of the thousands of applications it receives every year). When I was a visiting professor in Tokyo in 2017, my husband and I invited an asylum-seeking mother and her two children to stay with us for a weekend to get them out of the city, as we were on a lovely, tree-lined campus. She told us that she had been detained for several months in prison because her paperwork was a problem in customs. A pro-bono lawyer was finally able to get her out of detention and reunited with her children.

In Greece, I volunteered for an NGO in 2018 at Ritsona refugee camp on the Greek island of Evia, near Athens. The camp was intended for about 200 but housed over 1,000. When I was on clothes washing duty, I worked with volunteers to wash residents’ clothing in 20 small machines. Obviously, this was highly inadequate. When I was put at the camp “store,” the selection rules for clothing and shoes made no sense, leaving many residents without needed items even when they were in sufficient supply in the store.

The NGO in charge of the project employed young people with little experience in charge. None of them spoke Arabic, the first language of over 90% of the residents. Near the end of my time there, a potentially dangerous situation occurred when a male resident wielding a knife climbed on a rooftop screaming his frustration. The staff should have put the young volunteers on the first bus out, but even the director took a seat on the first bus, and university-age volunteers were left behind. I ended up counseling some of the young volunteers who were overwhelmed by what they saw.

I work with a NGO called NaTakallam that hires refugees and asylum seekers around the world to teach their languages and to explain their journeys. My Human Rights and Global Migration students interview them to learn first-hand stories. Many are from Venezuela, Syria, and Afghanistan. One disabled Venezuelan man tells the story of how his friends dissuaded him from going to a protest they were attending because of his disability.

All of them were killed at this protest.

And this is only half of the story.

These millions of people who would prefer to live a peaceful life in their countries, but who must flee terror and potential violence, torture, or death, encounter what? Desperate for safety, they hand over what they cannot afford — all of their money and possessions in hopes of reaching safety.

To whom? Thugs requesting outrageous sums to transport them in unseaworthy vessels, many of which sink (over 20,000 have died in the Mediterranean since 2014). Thug “coyotes” offering to take asylum seekers from Latin America to the US, with the result that hundreds die on the journey. Then there are unaccompanied children who ride on top of trains hoping to make it to the US. Many end up working with toxic chemicals in agriculture and animal processing plants. The lucky ones end up in US classes where they are immersed in English, exhausted by trying to understand the language without sufficient instruction.

Have you ever been in the position where you had no idea what was being said? I have. But for me, I knew that I would finally be returning to a place where the language was native for me and where I knew the customs. Not so for these children.

And then, these people, who must flee through no fault of their own, but because their countries are in a state of complete upheaval, face major discrimination. Politicians label them as potential criminals and terrorists (they are fleeing terrorists). Local citizens think that the Muslim asylum seekers and refugees may be terrorists. The newcomers work hard to learn the language and customs of their new country. Thankfully, there are organizations that help them. But in their day to day lives, they face many who do not believe they have a right to be where they are.

They do, however, have this right. The US, for one, seems to have forgotten its commitment to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), championed by Eleanor Roosevelt; and the Geneva Convention Related to the Status of Refugees (1951 and 1967 Protocol). Article 14 of the UDHR states that “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” The Geneva Convention states that “No Contracting State shall expel or return (“ refouler “) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

Violations are rampant, and they are racist. I am grateful that Ukrainian refugees are being supported by other countries, truly. But some of these countries have refused entry to Syrian and Afghan asylum seekers. Muslim and African refugees and asylum seekers face far more discrimination as they seek to relocate than did Bosnian and Ukrainian Christians.

And I see — gray. Struggling masses of people who are not cared for at best, and discriminated against at worst, as they just desire to live the safe life that most people reading this piece have. People want to ignore them, get rid of them, treat them like gray rats.

Research shows that when refugees and asylum seekers are welcomed and supported, they end up contributing to their new country in terms of work, social service, and taxes. They are grateful and they appreciate a chance for a new beginning. When native citizens treat them as scum, well, only then is when we might need to fear.

I know many remarkable success stories, particularly in the US and New Zealand, where I have worked the most. They have dealt with discrimination, but they have also had supportive people in their lives to help them rise beyond the prejudice.

A couple days ago, the New York Times reported on a passed House bill that would provide over $14 billion in military aid to Israel while cutting domestic spending. And I think to myself, as I watch this war unfold that is creating thousands more civilian deaths and refugees, why do we continue to let this kind of thing occur, and even aid it? Will we never learn?

Then the picture goes from gray to red.

Not all gray scenes are grim: Adrienne Beaumont has written a wonderful piece about the joys of gray weather travel.

And Brad Yonaka’s piece on manhole covers is a fascinating read.

Subhi Najar tells his personal story that reflects what I have written.