The Curiouser and Curiouser Conundrum

Why “Alice in Wonderland” is more relevant than ever.

“But it’s no use now,” thought poor Alice, “to pretend to be two people! Why, there’s hardly enough of me left to make one respectable person!”

Alice in Wonderland has long been a favorite subject to obsess over for bookworms and “normies” alike, something our great capitalist overlords have readily taken advantage of. There are Alice in Wonderland mugs, shirts, hats, coasters, mouse-pads, decorations, doormats, pens, erasers, and pretty much any other purchasable item in imagination to be found. London even has a dedicated bookstore.

What makes Alice… so popular, though?

I’ll skip the details of the story, as I assume most of us know it by now. If not, there’s far more skilled storytellers than me to delight you.

But I do want to delve a little bit in why Alice in Wonderland has become such a phenomenon. It’s a fantastic story, granted, and it’s very quotable, with many passages and much symbolism to transpose into our daily life. But that’s true about many stories, and I think there’s more to it.

Like Lord of the Rings and a handful of other tales that have grown and grown into larger-than-life phenomenons, Alice in Wonderland addresses a vital issue in our society, which I like to think of as the curiouser and curiouser conundrum.

The reason we like the story is that is seems to rail against a society that seems intent on keeping us down, keeping us “normal”. You’ve got all these characters who, rather than running away from their madness, seem to embrace it. And more importantly, much more importantly, they live in a world where they can do that.

Because the Mad Hatter would just be tragic if suddenly relocated to Paris or somewhere “normal”, you know?

The beauty of Alice in Wonderland isn’t that it brings forth all these fantastic characters like the fretful White Rabbit or the vanishing Cheshire Cat. It’s that it weaves for them a world that accepts them. A universe that doesn’t treat their individual peculiarities as something to be cured, medicated, or at the very least, carefully concealed. Something we’re critically bereft of in our own society.

I think the reason so many people find solace in the story isn’t simply that it presents characters madder than them, but that it suggests that what our world perceives as madness could just as well be normality, knocked on its head.

To top it all off, you’ve got the character of Alice who’s lovely and polite and sensible. In a way, she’s the icing on the cake, because although Alice comes from a point of great rigidity, from a world of manners and logic and rules, she tries to understand the residents of Wonderland. Rather than shun or deride them, Alice is kind and empathetic towards them. Something our own society, at the time of the story’s writing, particularly, was decidedly not.

And while our world has made great strides in its attitude towards mental health in the ensuing 160 years, it remains as rigid and unforgiving as ever in many other ways. Trapped inside a complex web of rules, of should and should-nots, interconnected, yet more isolated than ever before, madness lurks around every corner.

For a century that markets itself as all-inclusive and diverse, we’re anything but, if the rising levels on anxiety, depression, and isolation in our midst are anything to go by.

And here comes this story, propped up not only by its original literary panache, but also by the test of time (which tends to add a certain patina to most artistic creations). It reminds us it’s not us who are crazy. Might just be the world.

To be fair, in a world where so many of us seem to be suffering, it’s more plausible to assume the societal structure we’re building for ourselves is sick, and not the individual. Because if it was the individual, then it wouldn’t be so many of us experiencing these torments.

Another powerful lesson of Alice in Wonderland that ingratiates it to modern audiences is that there is great wisdom in the overlooked and discarded. That we ignore the wise Caterpillar or the teachings of the Cheshire Cat at our own peril, and ignoring them might end up costing us a lot more than bending the stupid societal rules that demoted these characters to outcast status in the first place.

I think Alice in Wonderland matters, still, because it’s saying these people — the outcast, the recluse, the conventionally “mad” — may have something important to teach us. That they are, in their unease, valuable. And is there anything more soothing and precious than one’s own intrinsic value, to reassure someone who’s struggling?

In a final effort to understand and define why Alice in Wonderland remains so popular, I examine my own reasons for returning to the story. And find that, in the deafening silence of not fitting in, it sends the reassuring message that you’re not supposed to. That there’s a place and a means of escape. That maybe you followed the white rabbit, and that’s why they’re now telling you your mind is broken.

That we know something they don’t. And therein lies our saving grace, and not, as we’ve been led to believe, damnation.

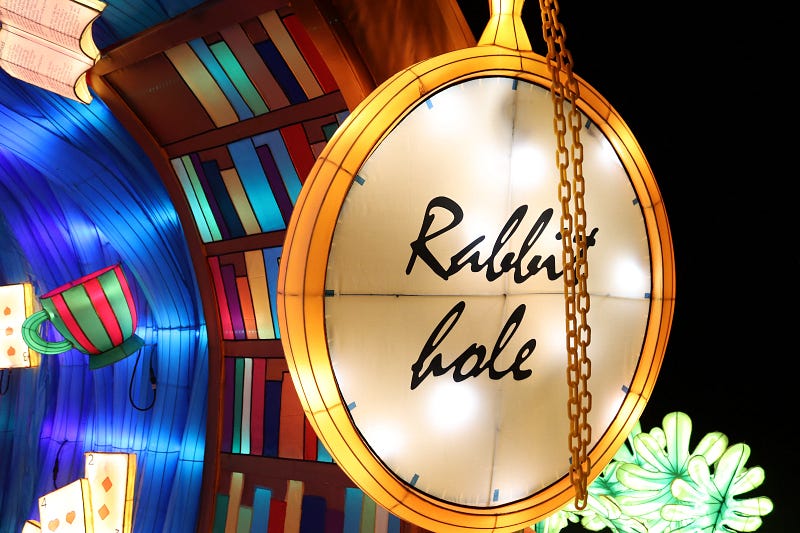

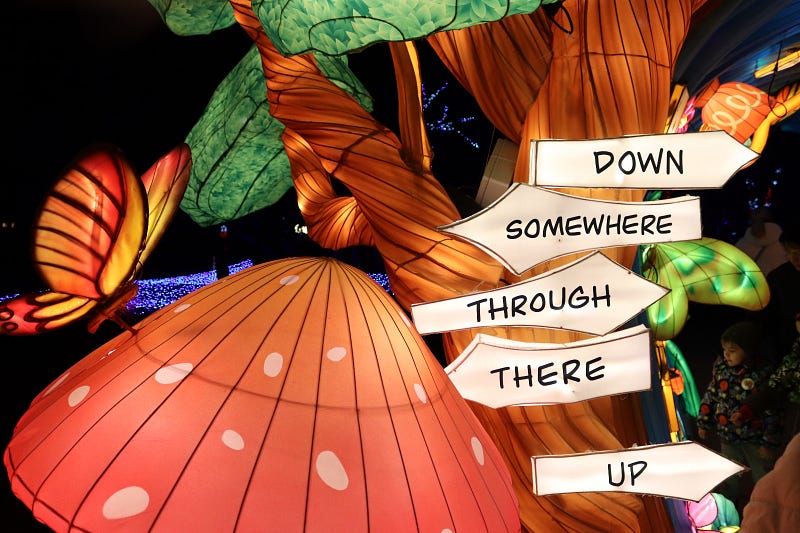

This little train of thought was prompted by a visit to the Alice in Wonderland Garden of Lights Exhibition in Bucharest, Romania (where all the pictures are from). Needless to add, all images are my own.

Thank you for reading.

I write stuff. Fiction. Psychology. Movie Reviews. Some poetry. The third (and final) volume in my fantasy series, The Warhound Trilogy, is coming out tomorrow. Pre-order it here, or check out the entire series for only ten bucks.