The Bible has a queer love story

Scholars are re-reading the book of ‘Philemon’

Near the end of the New Testament is a brief, enigmatic letter by the apostle Paul. What it’s about has been anyone’s guess.

The letter seemed to concern a slave being sent home to his master, Philemon. Many asked: Why was it even in the Bible? For centuries of Christianity, the book of Philemon was mostly disregarded.

Returning a slave was just business in ancient Rome.

Paul was not even doing theology, it seemed. Had a personal letter from the apostle snuck into the scriptures? That was the thinking.

But in the 4th century, Roman slavery was coming into disrepute, and the Philemon letter got more popular. If Paul was returning a slave to his master, Christians reasoned, then wasn’t he in favor of slavery?

That interpretation became the dominant reading for centuries. Philemon was seen as a statement that God endorsed slavery. The apostle sent a runaway slave back to his master. Therefore, slavery was divine.

Philemon helped Christians be pro-slavery.

That was their preferred position, of course. To be Christian was widely seen as a state of being white, powerful, and endorsing slave-owning.

During the Atlantic Slave Trade, Philemon was used to reinforce the pro-slavery Christianity. That history is told in a 2012 study, Onesimus Our Brother: Reading Religion, Race, and Culture in Philemon.

But was the letter really about a runaway slave being returned to his master? When modern Bible scholars took a look, the old Christian reading seemed less and less obvious.

The slave Onesimus, for example, was never said to have run away.

The letter provided a lot of clues to a situation that isn’t explicitly described.

One clue is: Onesimus becomes a Christian when meeting Paul. In context, however, this was odd. Typically in ancient Rome, slaves assumed the religious identity of their masters. For some reason, Onesimus had resisted Philemon’s Christianity.

In the course of helping Paul, Onesimus then accepted Jesus as his deity. Something had changed in his grasp of the theological situation. Then Paul sent Onesimus home with a note saying the slave was to be treated as “a beloved brother” (v.16).

To see his slave as family, as the scholar Michael F. Bird noted, “would have been quite scandalous and viewed as compromising the household order.”

The letter seemed like a closet of secrets.

Some of them are kept by the religion that, it turns out, had badly mistranslated the letter to remove gender ambiguity. In verse 10, in typical translations, Paul writes to Philemon about the slave:

“I appeal to you for my child, Onesimus, whose father I became in my imprisonment.”

Michael F. Bird translates the verse this way:

“I appeal to you concerning my child, Onesimus, whom I gave birth to during imprisonment.”

Paul wasn’t the slave’s father. He was Onesimus’ mother.

This is not at all surprising.

As Christians often don’t like to admit, Paul often presents as female (cf. Gal 4:19; 1 Thess 2:7; 1 Cor 3:2). A mother was a sacred figure, an aspect of God. And Paul writes with a lot of warmly maternal terms.

In verse 12 of the Philemon letter, Paul calls Onesimus “my very heart.” This word for ‘heart’, as Bird notes, could also be the word ‘womb’.

The apostle could be calling the slave: ‘my very womb’.

And as Bird notes, we see the apostle’s “intense motherly care for the welfare and well-being of his spiritual progeny.”

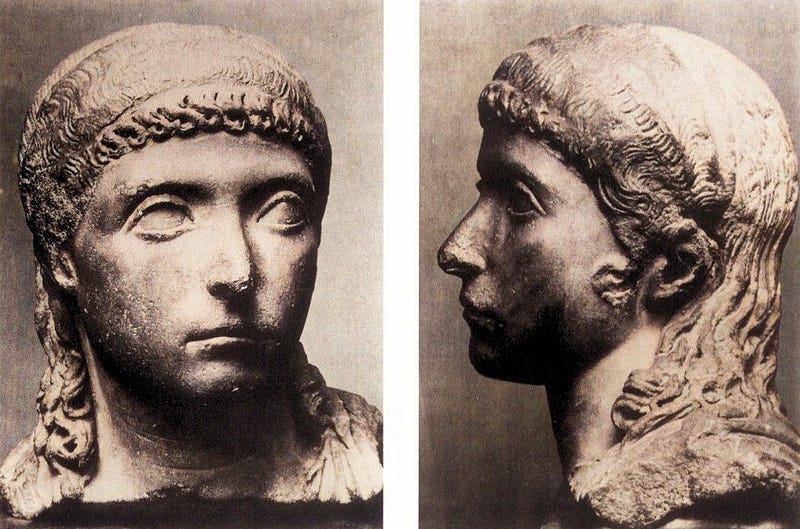

Philemon has been understood as a white, wealthy Roman man who was Christian.

To Christianity he was just a slaveowner who wanted his slave back. But there is a lot of information to another story. In the Bible, names are important clues to a character. The name ‘Philemon’ suggests the Greek word phileo, or ‘love’, and also philēma, which means ‘kiss’.

He seems to be a man made for love and eroticism.

The slave’s name, then, is said to mean ‘useful’. That issue is studied in a 2011 paper by Joseph A. Marchal, “The Usefulness of an Onesimus: The Sexual Use of Slaves and Paul’s Letter to Philemon.” It was updated in his 2019 book Appalling Bodies: Queer Figures Before and After Paul’s Letters.

Christianity had been misleading, Marchal suggests, in translating the slave’s name. Onēsimos suggests not ‘useful’ so much as “good-for-use,” “well-used,” or “easy-to-use.”

That suggests a rather specific context.

As Marshal notes, it’s a story written all over Greek and Roman literature. The poet Herodas has a character say: “I am a slave: use me as you wish.”

Slaves—not seen legally as persons—were often used for sex. The word “use” signaled that possibility. And Christianity would seem to know very well that the word “use” suggests sex. Note the standard translation of Romans 1:26–27:

“And likewise also the men, leaving the natural use of the woman…”

If translated on the same terms as Romans 1:26–27, Marchal suggests, the name ‘Onesimus’ means “good for intercourse.”

Onesimus was…a sex slave?

In that case, some suggestion might fill in. Philemon could be imagined as young and ‘pretty’. He would likely be a eunuch. In the Roman world, such a figure was called a delicatus.

They were very well known, including in Jewish communities. Herod the Great, the Jewish official who looms over the gospel narratives, kept a few of his own. It’s recalled by the Jewish historian Josephus:

“The king had some eunuchs of whom he was immoderately fond because of their beauty.”

Eunuchs were seen as sexually ambiguous.

For all the eunuchs in the Bible, Jews tended to look down on them. Eunuchs after all were unable to enter the Temple, per Deuteronomy 23.1. That was seen to be divine disavor.

The problem was, many Bible heroes are eunuchs! From the prophet Daniel to Jesus’ praise of eunuchs in Matthew 19:12 to the Ethiopian eunuch of Acts 8, it might not seem that eunuchs were bad at all.

In fact, they read as more spiritually capable. Is that unexpected? If not thinking as much about sex, family, lineage, etc., they may see the world around them more clearly.

Christian translations of the letter apply layers of gender to Onesimus.

In v.10, the translations have Onesimus called a “son” (v.10), but the word teknon means ‘child’. In v.16, Onesimus typically has his maleness reinforced repeatedly:

“He is very dear to me but even dearer to you, both as a fellow man and as a brother in the Lord.” (NIV)

All of this is made up. This phrase “fellow man” was an outright invention, and the Greek word adelphos, translated “brother,” is not a gendered term. It just means a sibling of either gender.

The actual presentation of Onesimus begins to look somewhat androgynous or gender-neutral.

The story is that Paul is sending a slave home.

But Paul writes that, going forward, Onesimus is to be regarded differently than he has been. As he writes, the slave is:

“…no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, a beloved brother (adelphon), especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.”

We’re being told that Onesimus and Philemon are close in body and spirit.

That is as close as anyone can be.

In some early manuscripts, Onesimus is not called Philemon’s “beloved brother,” but just “beloved.”

Paul’s counsel is for the two to love each other.

The slave is sent back to the master, with instructions that they now be family. In the matter of Philemon and Onesimus, it seems that Paul had been acting as a theologian after all. In the space of 335 words, he had invalidated slavery, and acknowledged a slave’s personhood.

Paul had likewise dismissed Jewish traditions about eunuchs, and concerns about homosexual or ‘queer’ sexualities. This might have been the grounds of Onesimus’ hesitation to convert to Christianity.

Then as later, differently-gendered people might not feel welcome in the faith. They may feel their very embodiment is ‘un-Christian’.

The plot of the letter might have been that Philemon had fallen in love with his sex slave.

They may wish to interact more as equals, as people rather than master and slave. The problem that both Philemon and Onesimus face is then quite clear. They are in violation of rules around Roman slavery.

Philemon has the further problem of being aware of Jewish traditions around eunuchs and homosexuality. The relationship is disapproved—and indeed, horrifying.

It may be that Philemon sent his slave to Paul in an effort to resolve these tensions. And after all, Paul was in prison needing help.

Paul asseses the situation, and sends the slave back with a message.

He says: Onesimus is a Christian, and he is family.

Early Christians kept needing reminders?

We seem to see Onesimus again in Colossians 4:9, where Paul notes he is:

“our faithful and dear brother (adelphō), who is one of you.”

This is Paul telling Christians that they must accept people who are legally slaves, and eunuchs? The message is: Onesimus is one of you. 🔶