Power: The Forgotten but Vital Training Variable

How to measure and improve your power to enhance health, capability and longevity

Many go to the gym to either build muscle, trim fat, get stronger, or improve their endurance. But there is one aspect of performance that is often ignored — improving power.

Power is a measure of work over time. It is how quickly you can generate force. Jumping, throwing, and swinging a golf club require power. In baseball, fastball velocity is one of the most important performance metrics a coach and scout looks at. In many track and field sports, your speed and jump height are all that matters.

Even if you aren’t an elite athlete, power helps you stand up from a chair, toss a bag of mulch in the back of a truck, or throw your kid in the pool.

Power is a primary marker of health and wellness, along with strength, VO2 max, and vitals. Without power, we can’t quickly generate force. In simple terms, force is a push or pull that can make things move, stop, or change direction. Your strength is how much force you can produce while power is how quickly you can produce it.

Power declines with age

Research shows our maximum power production for a typical person reduces by more than 50% between the ages of 20 and 80. It’s a steady linear decline due to a combination of losing muscle mass and muscle contraction efficiency.

A lot of research shows we lose muscle as we age, a process known as sarcopenia, and it is detrimental to our health. The fiber type that loses the most mass is type II fibers. These fast-twitch fibers are primarily responsible for strength and power, versus the type I slow-twitch fibers that are used for endurance-based activities. Type II are more powerful but fatigue quicker than Type I.

Both strength and power are vital for normal daily function. Strength gets most of the attention. Quadriceps strength is a primary predictor of mortality according to research from the American Journal of Medicine. Additional research suggests hip flexor strength, is a primary factor responsible for the progression of functional capacity decline. The hip flexors are the muscles in the front of the hip that help you pick your leg up.

Power loss may be more problematic. Power output is more responsible for functional declines than strength according to research from Sports Medicine. Without it, standing up from the floor or lifting a suitcase into the overhead compartment becomes impossible.

So, training for power in the short term may help you play from the blue tees or split a log in hal fon the first swing but it will also keep you physically healthy longer. Before you develop a training plan to enhance power, it is beneficial to know where you currently stand.

How to test your power

There are several ways to test your power. Like strength, power is specific to your target muscles and movement. There will be a skill component.

Olympic weightlifters generate immense amounts of power and are some of the strongest people in the world, pound for pound. That doesn’t mean they can execute a 100-mph fastball or tennis serve. A baseball swing, tennis serve, javelin throw, and snatch all require substantial power, and they all involve fine-tuned motor skills one does not develop simply by focusing on power.

Why is this important for testing power? The best power tests are the ones that involve the least amount of skill. If you want to have a general understanding of your power production, use one of the following tests

Sit to stand

This is the most basic of the assessments and one I use with many of my physical therapy patients.

Here’s how it works: Start in a chair, fold your arms across your chest, and stand up completely, then sit back down. Repeat this sequence five times as quickly as you can. Measure the total time it takes in seconds. Here are your targets for time:

- Young Adults (20–59 years): Around 8–12 seconds is considered normal.

- Older Adults (60–79 years): Approximately 12–15 seconds may be considered typical.

- Elderly Adults (80+ years): Completion times may vary, but generally, 15 seconds or longer might be indicative of reduced functional mobility.

These are general ranges. If you have sufficient power, you should fall within those range. But what if you want more detail? What is the amount of power you are generating?

Cycling

Testing your power on a stationary bike is a straightforward process. First, make sure the bike is set up just right for you. Check the seat height and handlebar position to ensure comfort. If your bike has a power meter (most do), follow the instructions to see how much power you’re putting into your pedals. Sometimes you have to cycle through the data shown on the screen, such as the calories, distance, and time.

Start with a good warm-up by pedaling at a medium speed for about 5–10 minutes. Then, do a short but intense power test, like a quick 5-minute sprint or a 20-second burst of energy. Focus on pedaling strongly during the test. Look at the power number on your bike’s display and note any other details, like how long you pedaled or how far you went. This information helps you understand your power and fitness level on the stationary bike.

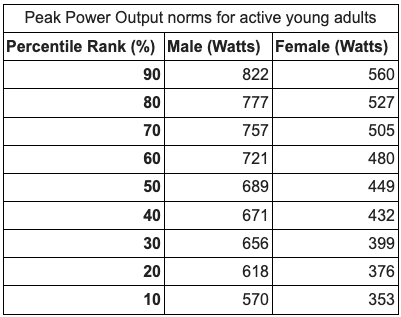

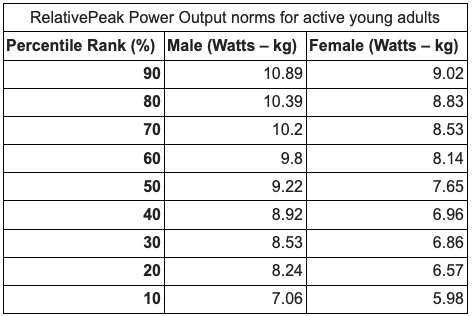

Here are some data points to shoot for based on previous research:

Jumping

The vertical jump is a simple and effective way to measure power. To begin, stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and measure your reach height by extending your arm straight up against a wall. This initial measurement helps determine the starting point for your jump. Then jump as high as you can, reaching for the sky, and marking your top height. You can have a partner watch, use a video camera, or mark the wall with a piece of chalk or sticky note in your hand.

The height you reach indicates the power in your legs. Make sure to bend your knees and swing your arms to maximize your jump potential. Vertical jump tests are commonly used in sports and fitness to evaluate explosive strength. Here are some data points to aim for:

- Average jump height for untrained males: 16–20 inches (40–50 cm)

- Average jump height for untrained females: 12–16 inches (30–40 cm)

- Average jump height for trained males: 24–28 inches (60–70 cm)

- Average jump height for trained females: 20–24 inches (50–60 cm)

Upper body

For upper body power, you have several options. Rowing ergometers can track watts and you can focus on max output or sustained pulls, similar to a stationary bike.

In physical therapy, a seated shot put throw is commonly used, measuring the distance thrown and using a side-to-side comparison.

Like the lower body, you can simply track progress with movements that require power, such as the snatch, jerk, and power clean.

That’s enough about testing, let’s see how you can improve your power output.

How to improve your power

The best way to become more powerful is to move quickly. You can start by performing each rep in the gym as fast as possible, regardless of the weight. The goal is to stimulate as many motor units (the connection point between the nerve and the muscle) as possible.

The rapid movement should occur during the concentric phase of muscle contraction. That is when the muscle is shortening. For example, during the up phase of a squat or the curling phase of a biceps curl. The lengthening portion (eccentric phase) should be controlled to maximize muscle strength and growth, as you tend to want more time under tension to build muscle.

If you are lifting very heavy weights, approaching your max lift, or lifting close to fatigue, you won’t be able to move the weight quickly. That doesn’t mean power isn’t trained. You should still try to contract the muscle and move the weight as quickly as possible.

For maximizing power results, you are better off pulling back a little on the resistance so that you can move quickly. Studies show peak power is generated around 70% of your 1 rep max. So, if your max squat is 300 pounds, moving as quickly as you can with 210 pounds will maximize your power output.

Know that power training, like heavy strength training, is both safe and effective in older adults.

If you have a stationary bike that measures power (most gym versions can) then you can play around with the resistance until you find the sweet spot for generating peak and high levels of sustained power. Train to improve both.

You won’t be able to sustain peak power for long. If you are cycling at peak power, performing max effort jump training (not repeated low-intensity plyometrics like jump rope, as they do not improve power), or sprinting, you will need long rest breaks.

As with strength development, you need longer rest breaks ranging from 3–7 minutes between sets of exercise to allow your muscle to restore most of its ATP, the muscle’s energy source. There is benefit to training in a fatigued state, as sporting events often require high power output when fatigued, but training in a fresh state will allow you to maximize peak results.

Measure your improvement using the earlier tests. Power and strength are closely aligned. As your power improves, your strength will likely improve as well. Being more powerful won’t automatically allow you to hit a ball farther or run faster, but it will provide the physical foundation necessary to improve those skills.

Being more powerful will improve your overall health and longevity as well.