New Zealand’s Treasure Box

Wellington’s innovative Te Papa Museum

Lambdon Quay, in the heart of Wellington, is an odd name for a street that is 250 meters from the water’s edge. A quay is a dock area. It’s supposed to be on the shoreline. But in 1855 an massive earthquake uplifted the land beneath New Zealand’s new capital city by 1.5 meters and left the quay high and dry. The newly emerged land immediately became prime real estate, and once they got the idea, city planners and developers carried on, reclaiming more and more land in the susequent century by infilling the shallows.

Right on water’s edge today, built on newly reclaimed land, is the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Te Papa means “Treasure Box” in the native Māori tongue. It’s not just the land beneath the museum that has been reclaimed; the art, the history, and the narrative have also been reclaimed. Previously, this offical custodian of New Zealand’s past was known as the Colonial Museum. But Te Papa is something new and unique, at least in my experience: A de-colonizing museum.

In countries with a colonial past, museums usually tell the nation’s history from the perspective of the dominant culture as “we” and the indigenous peoples as “them.” Te Papa tells the story of the Māori and the story of Pākehā (European settlers and their descendants) as the story of “us, together.” In this way it lives up to the founding document of New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 as a convenant between the British Crown and the more than 500 Māori chiefs, as a partnership between two peoples.

The treaty was violated hundreds of times by the colonists since signing, but in the mid 1970’s, in response to Māori protests about the continuing takeover of their lands (including a 1975 Ghandi-style protest march over 1,100 kilometers, led by the indomidable 79-year old Whina Cooper) the New Zealand government agreed to set up a tribunal. The Waitangi Tribunal has since addressed over 2,000 claims, and recommended many changes that have set the government back on a path to genuine partnership. The original Waitangi Treaty is on display at Te Papa, in a prominent place of honor on the main floor.

As an author and storyteller, one of the reason museums fascinate me is because I see them as the way a society tells the story of itself to itself. If the “artefacts” of a minority indigenous community are shoved into cases in a back room, that says something about their place in the dominant culture’s narrative. Even if the artefacts are prominently displayed, but treated like exhibits of ancient Egyptians or other exotic “dead” peoples, that framing tells you something important. To turn another’s culture into a collection of objects that can be defined and displayed is rather like capturing a butterfly fly and sticking a pin through it. Preserved as part of a collection, it has no more life.

I was first sensitized to this just a year ago at a museum in Northern Norway that was run by the indigenous Sāmi community. Their most prominent exhibit was a ritual drum, which has been returned to the Sāmi people by government of Denmark in 2022. To the Sāmi, a ritual drum is not an artefact; it is a “non-human person” with a spirit and will of its own. Having the drum returned was like having an ancestor brought home. The drum was given its own special room, and could not be photographed — treated more like an honored guest than an object. It shocked me to suddenly realize that museums all over the world hold “artifacts” in their collections that have different and deeper meanings for the living communities that they were taken from. (I’m very proud to add, my niece, Claire Grenier is currently doing a M.F.A. in museum curation with the intention of addressing exactly these kinds of issues).

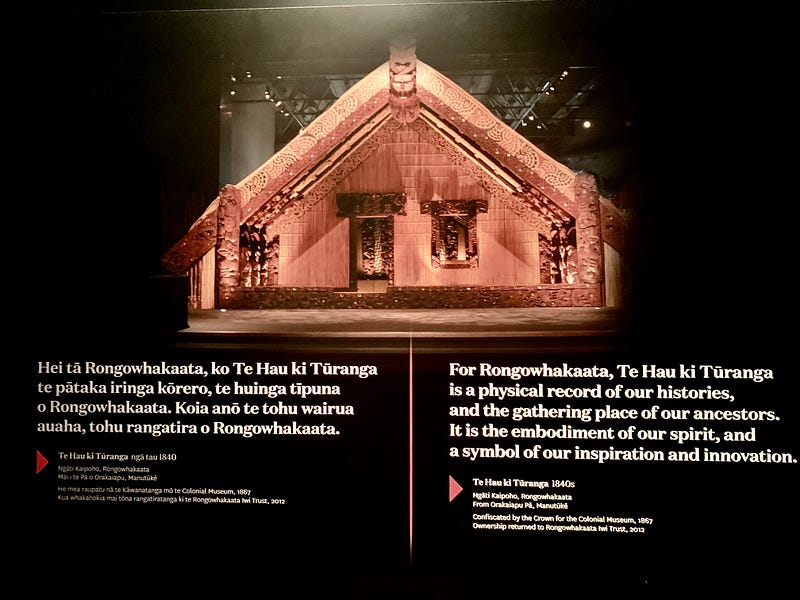

The most amazing example of the shift of narrative in Te Papa is the exhibition of the historic Māori gathering place, Te Hau ki Tūranga, of the Rongowhakaata tribe. The stucture dominates the main display room of the Māori history section. For Māori tribes, these buildings function as a combination church, museum, and memorial, town hall and community center all under one roof. In 1867, this exact building was simply confiscated by the government. Without asking the consent of the tribe, it was dismantled, taken from tribal land to Wellington, and then reassembled inside the Colonial Museum. It sat there on display for more than 100 years, as an example of a Te Hau ki Tūranga.

Can you imagine a group of outsiders coming into your home town, ripping apart the main church and carting the pieces off to put it in their museum?

Only in 2012 was ownership returned to the Rongowhakaata tribe. They have agreed to let Te Papa keep and display their building, but also to tell the horrific story of how it was taken. Importantly, the building’s status as a sacred space has been restored. One cannot walk inside, and no photographs are allowed. That is a new narrative of mutual respect and collaboration that also owns the wrongs of the past.

The museum also features an impressive temporary exhibit dedicated to the Waka, the Maori canoe, and specifically to the large canoes that were reconstructed for a massive ceremony in 2020 to commemorate the 180th anniversary of the Waitangi Treaty. These were massive boats, holding as many as fifty paddlers, decorated with intricate carvings and oramented with feathers. Each tribal group built and paddled their community’s canoe to the cermony at Waitangi. Prime Minister at the time, Jacinda Ardern, also took part. Her rowing in a Māori canoe filled with young New Zealanders symbolized her government’s commitment to a future in which settler and Māori communities pulled together. After all, they are all in the same boat.

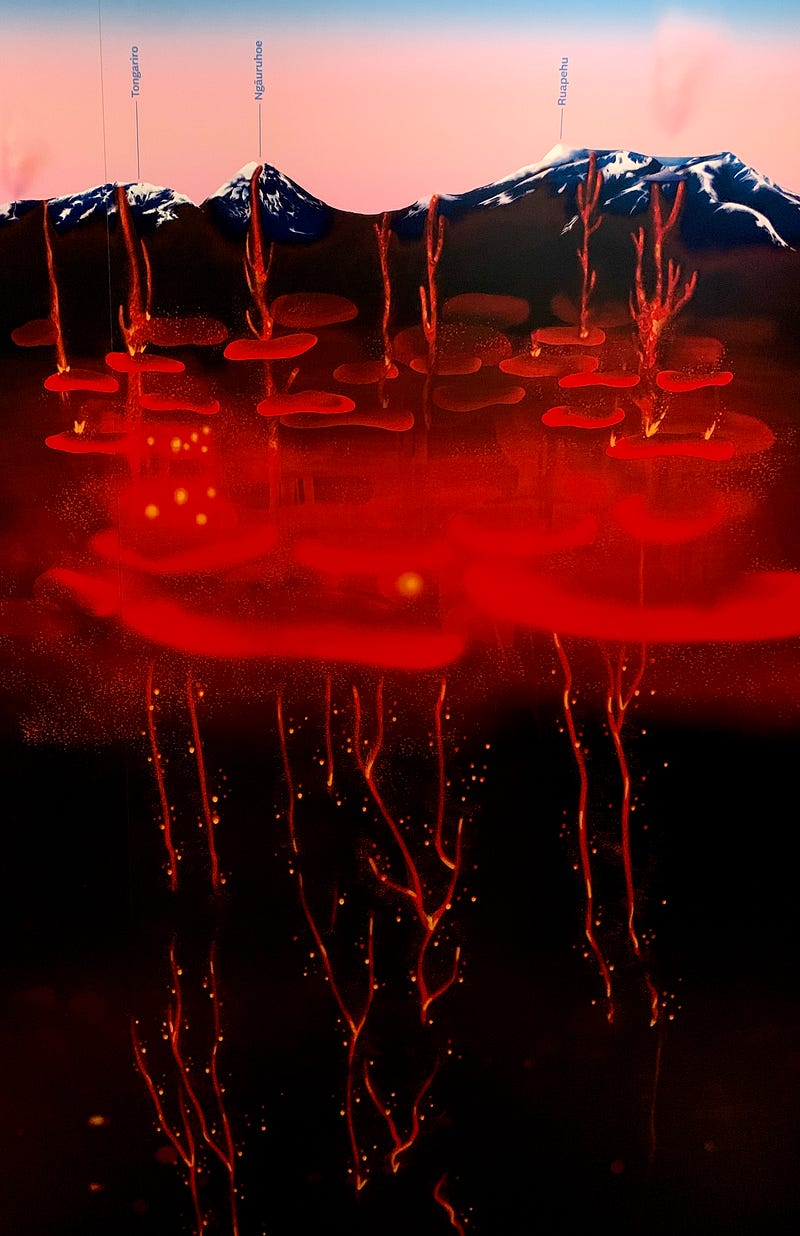

I was also struck by the portion of the museum dedicated to natural history, and not just because the placards were in both English and te reo Māori. (Te reo Māori was only made an offical language of New Zealand only in 1987). As well as two languages, the museum provided two complementary narratives. For example, there was a prominent exhibit titled Awesome Forces on earthquakes and volcanic eruptions (both of which are very real dangers for residents of New Zealand). Side by side with the science, the museum tells the story of Rūaumoko, the Māori god of earthquakes and volcanoes. As the museum website explains:

According to Māori tradition, earthquakes are caused by the god Rūaumoko (or Rūamoko), the son of Ranginui (the Sky) and his wife Papatūānuku (the Earth). Rangi had been separated from Papa, and his tears had flooded the land. Their sons resolved to turn their mother face downwards, so that she and Rangi should not constantly see one another’s sorrow and grieve more. When Papatūānuku was turned over, Rūaumoko was still at her breast, and was carried to the world below. To keep him warm there he was given fire. He is the god of earthquakes and volcanoes, and the rumblings that disturb the land are made by him as he walks about.

A trail of Rūamoko’s footsteps winds through the geological explanations of tectonic forces and subterranean magma resevoirs. I appreciated how seamlessly the two narratives of myth and science were woven together in the exhibit hall— not as if one was true and the other false, but rather, that these two ways of connecting with the reality of these mighty and terrifying forces far beneath our feet.

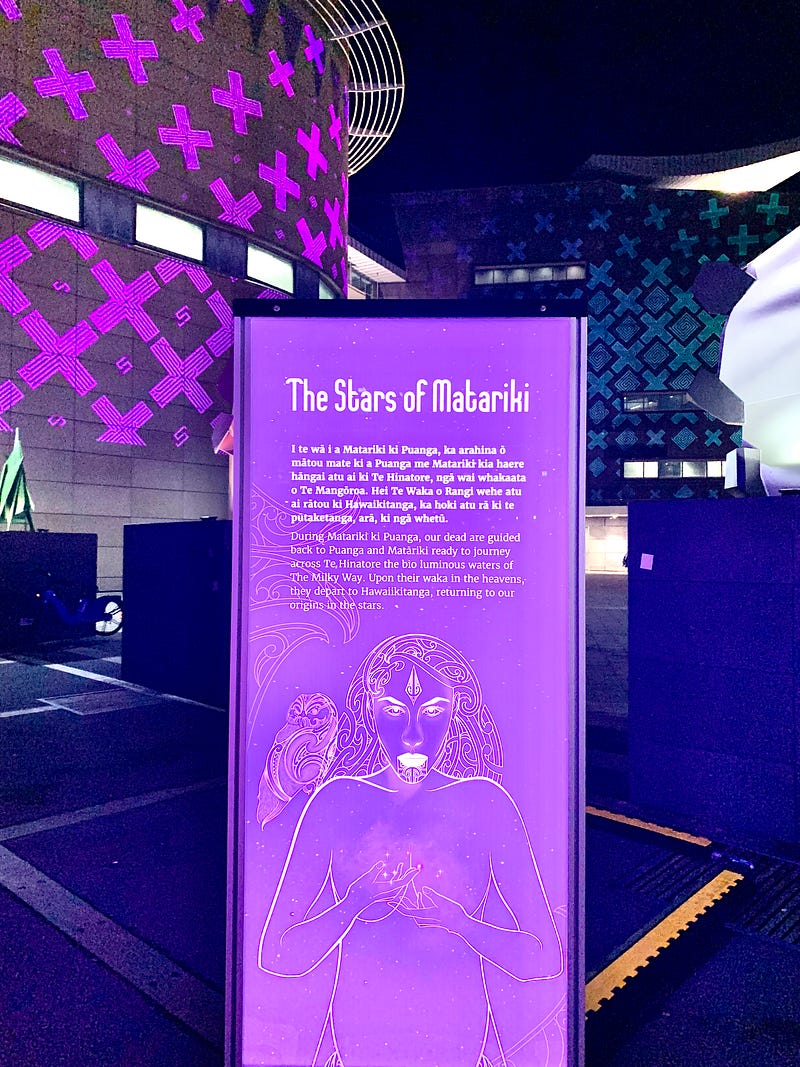

The museum also had a special area for children which, at the time of our visit was devoted to events and activities celebrating Matarika, the Māori New Year. This is a time of year when tribal communities gather to remember their ancestors, something like the Mexican “Day of the Dead.” In 2022 Matariki became an official public holiday in New Zealand. It is the first public holiday that marks a Maori holiday. Traditionally, Māori take two weeks to gather and celebrate at this time of year, which varies according to the lunar calendar. A nation-wide, two-week school semester break now takes place aligned with these dates.

In the run up to Matariki, an entire outside wall of the museum has been turned into a dazzling Matariki light show at night, combining the work of traditional Māori artists with modern light-projection techniques. Illuminated posters next to the wall explain the legend of Matariki, also known as the constellation of the Pleiades, and the meaning of each star as a specific celestial divinity from Māori mythology. The museum events and other celebrations were not simply for tribal children, but were framed inclusively for every child, and portrayed as part of their identity as New Zealanders.

From the museum website:

Matariki is the star cluster most commonly known across the world as Pleiades. …Around the world there are many names for this group of stars. In Japan, it is called Subaru, which means ‘to come together’. In China it is Mao, the hairy head of the white tiger, and in India it is known as Krittika. In Greek mythology they are known as the seven sisters, and in Norse mythology the Vikings knew them as Freyja’s hens…For many cultures, these stars are connected to celebration, planting, harvesting, weather, and life. For Māori, the rising of Matariki signals te Mātahi o te Tau, the Māori New Year. The appearance of Matariki in the morning sky is a sign for people to gather, to honour the dead, celebrate the present, and plan for the future.

As well as designating Matakiri a national holiday over a long weekend, the goverment also encourages all New Zealanders to use this special time to gather as families and to:

Remember the past, honor the dead, celebrate the present, and plan for the future.

Truly, this is a blueprint for de-colonizing that countries everywhere could well adopt.

***

Hey travel-lovers, please check out my new book on the art of slow travel: