The Bible’s queerest story? The book of Ruth

An Old Testament book finds God in an LGBT mood

At Christian weddings, the bride and groom often recite a speech from the Bible. The verses Ruth 1:16–17 have married many couples.

Brides and grooms, endlessly, say the lovely words:

“For where you go I will go, and where you lodge I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God.”

It’s a bit ironic, as it’s a speech between two women.

Could the Bible’s story of Ruth and Naomi be a queer love story?

I must say, when I first heard the idea, I was surprised. Surely not in the Bible. But as I’m going through the scholarly literature on the book of Ruth, which often notices the weird gendering, I have to notice facts.

In Ruth 1:14, Ruth “clung” to Naomi, just as a man “clings” to a wife in Genesis 2:24.

Then the very fact of two people loving each other is very unusual. The reason that the speech of Ruth 1:16–17 is read at weddings is because no such language is ever found between male-female couples. In the Bible, married couples don’t typically love each other. As the scholar Athalya Brenner has noted, the story of heterosexual love in the Old Testament is “sad and limited.”

This is no surprise at all. In the ancient world, marriages were not based on love. Women were bought as wives. Typically couples barely knew each other when getting married, if indeed they’d even met.

But Ruth and Naomi love each other.

Ruth’s situation is that she’s a Moabite woman whose Israelite husband died. She expresses no grief about that, interestingly. What she wants to do is stay with his mother as an act of devotion.

By her love for Naomi, Ruth takes on Naomi’s deity. Is this an example of the conversion-by-marriage that Paul speaks of in 1 Corinthians 7:14?

“For the unbelieving husband has been sanctified through his wife, and the unbelieving wife has been sanctified through her believing husband.”

Was it lesbian? Still not quite sure, I survey Christian art that depicts the two women, and am surprised at how often there’s a clear ‘queer possibility’. It’s as if the religion has secretly believed Ruth and Naomi were a romantic couple.

As the story moves along, Ruth and Naomi journey to Bethlehem.

This is Naomi’s original home. They find themselves on land owned by a man named Boaz, a wealthy Israelite who is a kinsman of Naomi. He is often read as an ‘eligible bachelor’, but Boaz is kind of an unusual man.

He’s praised as a “man of power and substance” (2:1). But these qualities aren’t created by a wife or children. He seems to be mature or older, but unmarried.

In the Bible, a man often marries a woman after he find her “beautiful,” but Boaz never says this about Ruth. As Brett Krutzsch writes in a 2015 paper, “Un-Straightening Boaz in Ruth Scholarship,” Boaz is never seen expressing any sexual attraction for women.

He’s mostly seen hanging around with men.

There’s a lot of legal subplot.

Christian readers who find a love story happening between Ruth and Boaz are just not tracking the facts. Naomi once lived in Bethlehem, and moved to Moab because of a famine. When all her male relatives died, she entered a kind of legal limbo.

Naomi’s family still owns property in Bethlehem (cf. 4:2), but without a male head of the family, she can’t even sell it. As Agnethe Siquans notes in a study of legal terms in the book of Ruth: “a woman without male relatives was not granted any legal status.”

But there’s a possibility for Naomi regaining status. Her son, Ruth’s dead husband, is not totally dead. By the law of the Levirate marriage, a widow whose Israelite husband has died can be impregnated by a male relative. A resulting son will be viewed as the dead man’s heir.

An idea forms: If Ruth pops out a son by any kinsman of her dead husband, this son will become the new head of the family.

There’s one problem: Ruth is Moabite.

God has told the Israelites to avoid this tribe of people (Deut 23:3–4). Moabites read as ungodly and sexually dangerous. The line began when Lot’s daughters raped him back in Genesis 19:30–38, and Moabite women had caused a lot of trouble in Numbers 25.

Boaz tells the local men to steer clear of Ruth and Naomi. This is an act of consideration for both of them. We’re remember that Boaz is an outsider as well. He’s not totally Israelite, in that he’s a descendent of Rahab the Harlot, the prostitute of Judges 2–6. Non-Israelite women with unusual sexual energy are part of his story.

But the feeling we get is that Ruth is seen as trouble. And both women are trouble. Naomi hatches a plan—like the one hatched by Lot’s daughters in Genesis 19, or by Tamar in Genesis 38. They plan to get a son out of an Israelite man who isn’t aware of what’s going on.

Boaz had been drinking and fell asleep.

On Naomi’s instruction, Ruth goes to him, essentially, to rape him. Boaz is awakened by Ruth’s approach—where Lot, in a similar position, had remained asleep.

Boaz is “startled” or afraid (3:8). He’s certainly not feeling the sexy. In a 2013 paper on Boaz’ odd masculinity, Hugh S. Pyper writes of the scene: “As it progresses, it definitely casts Boaz in a rather queer light.”

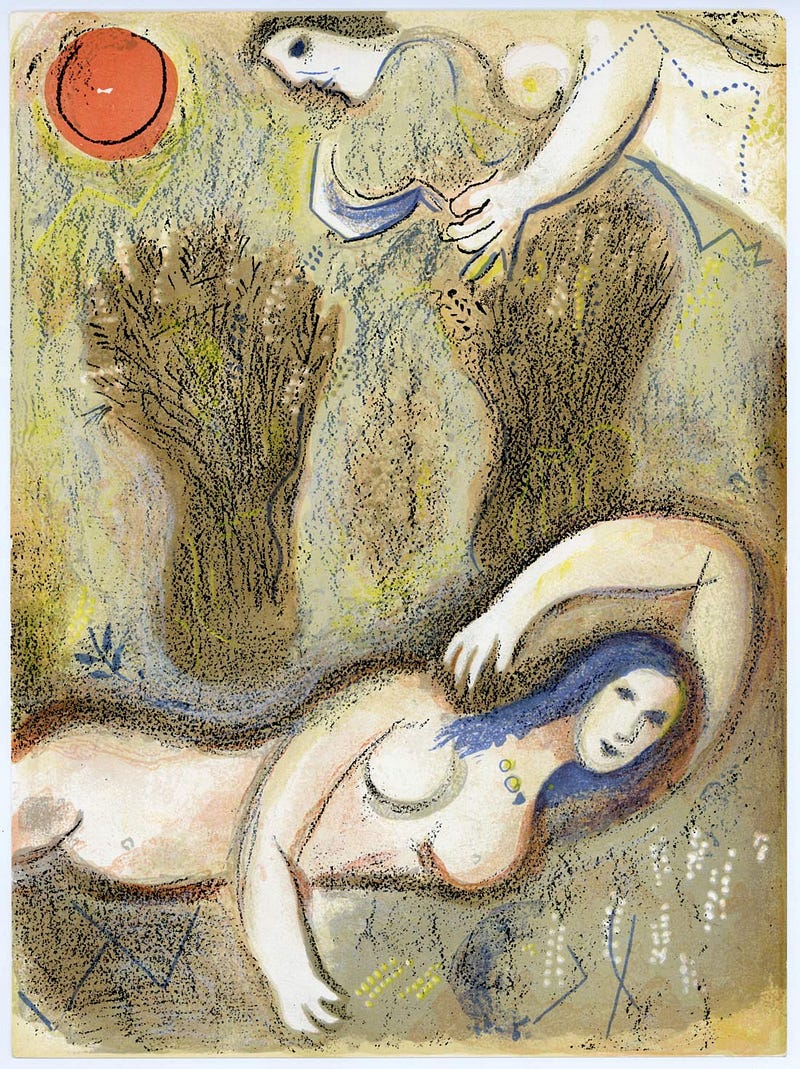

The 1958 painting by Marc Chagall, Boaz Wakes Up And Sees Ruth At His Feet, nicely captures the oddness. This is no display of heterosexuality.

Boaz wises up quick.

He realizes the scheme the women are pulling. He knows he’s a relative of Ruth’s dead husband. He knows a kid would become that man’s child.

He knows as well: If Ruth bears a son, it’ll restore an Israelite family line—a service that God will honor. We’d remember that Onan in Genesis 38, when refusing the service to Tamar, was struck down by God.

He would also know the child would be half-Moabite, and that is sure to be a problem.

Boaz has an idea. He marries Ruth!

This is an extreme solution, not required by the law of Levirate marriage. And it’s scripturally troubled, breaking the rules against Israelite intermarriage. But Boaz, as a wise man, weighs the ‘rules’ against the needs of humans, and the unusual fact he sees before him of Ruth, through her connection with Naomi, having become a Yahweh-follower.

This was never a heterosexual love story.

Boaz announces the marriage publicly: “I am also acquiring Ruth the Moabite, the wife of Mahlon, as my wife, so as to perpetuate the name of the deceased” (4:10).

This was done to seal the child’s identity as an Israelite. It was a practical solution, as Krutzsch writes, that is:

“…a formality among two people in ancient Bethlehem who needed to fulfill societal expectations to enter marriage and produce progeny.”

That the boy is half-Moabite, however, remains a problem. Not even Boaz as the legal father can ease that situation. In the Bible, over and over, spiritual identity is passed through the mother.

Only when Naomi stands in as the mother, nursing the infant herself, is the boy accepted as an Israelite. People say: “a son has been born to Naomi” (4:17).

The boy then has two mothers, Ruth and Naomi, and two fathers, Mahlon and Boaz. And a phenomenon of biblical proportions occurs. The split Abrahamic line, from Israelite to Moabite, is consolidated.

This son of Ruth and Boaz becomes the grandfather of David, as puts them all in the line of Christ (Mt 1:5).

What had seemed messy…is messianic.

And that’s the Bible!

Single mothers. Ladies in love. Men raped or used. God keeps it weird. And we couldn’t forget that a bond between Ruth and Naomi is, throughout, the driving force.

Their strange love made the plot happen. By being devoted to each other in some intense, unexpected way, they become “biblical.” 🔶