Affected by leprosy and scabies: Egyptian Antisemitism in Antiquity

Accusing Jews of misconduct and all sorts of crimes is as old as time itself. Ancient times. The list of wrongdoings was concocted by Egyptians, confirmed by Greeks, and the Romans had great fun with it. That’s what Egyptian antisemitism looked like.

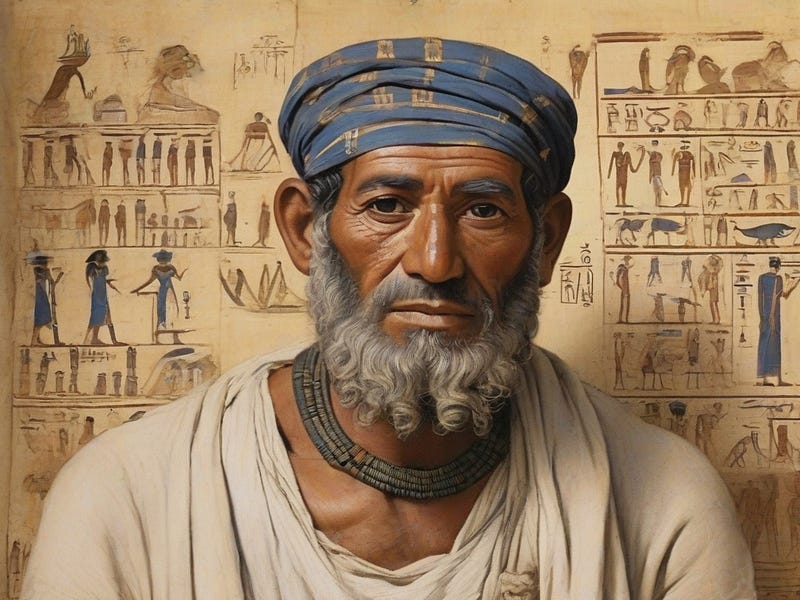

Jews stick together, dislike others, commit ritual murders. And by the way, they are lepers and spread contagion. This isn’t an excerpt from the forgeries of the Tsarist Okhrana or from Nazi pamphlets, but rather the opinion of historians who wrote in Greek about Egypt. These and other ‘golden thoughts’ of ancient writers were collected by the Jewish historian Josephus Flavius (born around 37 AD). He was an eyewitness to the great Jewish uprising against the Romans in 66 AD. After the war ended, in gratitude for services rendered to the Romans, he was granted Roman citizenship and permanently moved to the capital of the world at that time.

Apart from ‘The Antiquities of the Jews’ and ‘The Jewish War,’ he wrote a lesser-known work called ‘Against Apion’ there. In it, he aimed to dispel the stereotypes about Jews circulating in Greek literature, to showcase their absurdity, and to unveil the laws of Jewish tradition. The titular Apion was a grammarian (a mid-level teacher) in Alexandria who later, during the reign of Emperor Tiberius, moved to Rome. Apion’s most famous work — unfortunately, not extant today — was ‘Aigyptiaka’ (Egyptian Histories) written in five books. In the third and fourth books of this uncritical work on the history, culture, and religion of Egypt, Apion dedicated portions to Jews. It was precisely this part, filled with anti-Jewish stereotypes, that became the basis for ‘Against Apion’ by our Josephus.

The Exodus of the Afflicted

Before Flavius addressed the views of the titular character, he confronted other Greek-writing Egyptian historians (whose works are also lost).

Manetho (3rd century BC), an Egyptian priest from Heliopolis, wrote that Moses — just like himself — was a priest and originally called Osarsiph. When Pharaoh Amenophis desired to see the gods with his own eyes, he had to purify the country of leprous and unclean people. All the impaired ones were sent to the quarries. Then, with the pharaoh’s consent, they settled in the city of Avaris, once abandoned by shepherds.

Osarsiph led these unclean individuals and enacted laws forbidding worship of the gods, killing and eating animals sacred to the Egyptian religion, and having no relations with outsiders. Later, the new leader sent an embassy to Jerusalem, urging its inhabitants to join a common expedition against the Egyptians. His words found fertile ground, and the lepers, along with the invaders, collectively devastated Egypt, destroying temples and turning them into kitchens where they roasted sacred animals. Osarsiph allied with the outsiders and changed his name to Moses.

Devastation in Egypt

The tale of rebellion and the city of Avaris refers to the invasion of the Hyksos, who ravaged Egypt in the so-called Second Intermediate Period (17th/16th century BC). Manetho does not explicitly mention Jews among the afflicted sentenced to work in quarries. Moses-Osarsiph established new laws contrary to the official religion, and those who accepted it — the rebellious lepers — were mostly Egyptians themselves. Flavius found a similar story in the history of Egypt by Chairemon, a Stoic philosopher and Egyptian priest from the 1st century AD. Pharaoh Amenophis, who wanted to rid the country of all afflicted ones, expelled 250 thousand people. At their head were Tisithen (Moses) and Joseph (Petesef). The exiles allied with people whom the pharaoh did not wish to release from Egypt, and together they revolted. The ruler had to flee to Ethiopia. Only his son expelled the Jews to Syria.

Similarly, in the completely unknown history of Lysimachus (who lived between the 3rd century BC and the 1st century AD), Flavius found this account of the departure of Jews from Egypt: ‘During the reign of the Egyptian king Bochoris, the Jewish nation afflicted with leprosy, scabies, and suffering from some other diseases took refuge in temples, living a beggarly life. Because a multitude of people fell ill, a famine struck Egypt.’ The king then went to an oracle, which instructed him to exile the unclean and godless to the desert, while the leprous and scabby were thrown into the sea. Those who escaped the slaughter convened in the desert to decide what to do next. That’s when Moses advised them to go to the nearest inhabited areas, show no kindness to anyone, and destroy encountered places of religious worship. The Jews arrived in a land called Judea and founded the city of Hierosyla (literally meaning ‘the city plundering temples’). Only later, out of shame, did they change its name to Jerusalem.

The Worshipers of the Donkey

The Greek intellectual Apion consistently demonstrated an anti-Jewish attitude, not only when writing about Jewish history but also about their religion and the Jews residing in Alexandria. He denied them the title of ‘Alexandrians’ and any rights to citizenship in that city.

Apion emphasized that the Jews had not produced any renowned men in any field. He mocked the custom of circumcision and the prohibition of consuming pork. In his ‘Egyptian Histories,’ he reiterated the tale (although more elaborated and specifically concerning Jews) of Moses and the lepers. According to Apion, the Jewish legislator — an Egyptian priest from Heliopolis — led 110,000 ‘lepers, blind, and lame Jews’ out of Egypt. They traveled through the desert for six days until ‘they developed sores in the groin, and for this reason, upon their fortunate arrival in the land called Judea today, on the seventh day, they rested and called that day “sabbath,” retaining the Egyptian term because the Egyptians call the groin afflictions “sabbo.”’ Then Moses went to Mount Sinai, where he remained in hiding for 40 days, and upon descending, he bestowed laws upon the Jews.

Apion also maintained that the Jews placed the head of an donkey in the Jerusalem temple and worshipped it. When Antiochus Epiphanes plundered the sanctuary (168 BC), he allegedly found a golden head of an donkey there, symbolizing immense material value. Such an accusation was not new in Greek literature. Around 200 BC, Mnaseas from Patara in Asia Minor, a philologist and student of Eratosthenes, an educator at the court in Alexandria, wrote about it. Apion, on the other hand, read about the donkey from Poseidonius of Apamea, a renowned philosopher and historian from the 2nd/1st century BC. Interestingly, this accusation would later be applied to Christians as well. Graffiti discovered on the Palatine Hill in Rome depicted a crucified man with the head of an donkey, with the inscription below: ‘Aleksamenos worships his god.’ Christian Aleksamenos was accused by his peers of worshipping a divine donkey.

Ritual Murders Among Jews

Jews were also alleged to commit ritual murders and consume human flesh. Apion, cited by Josephus Flavius, claimed that Antiochus found a bed in the temple where a man lay. Next to it was a well-set table. It turned out that the man lying there was a kidnapped Greek. The Jews prepared him for sacrifice, following ‘a secret law that commanded them to feed him in this manner. They do this every year at a designated time.

They abduct a Greek foreigner, fatten him for a year, then lead him into a forest, kill him, and according to their rites, offer his body as a sacrifice and consume the flesh.’ This description seems to be Apion’s invention. In other sources, there is no mention of the mysterious Jewish God demanding offerings from foreigners. In this way, Jews became a threat to the entire civilized world, according to Apion. Moreover, Apion wrote that the Jews swore not to show any kindness to representatives of other peoples, especially Greeks.

Ironically, the xenophobic anti-Jewish Apion ended up with an ulcer on his genitals toward the end of his life and had to undergo circumcision. He died in excruciating agony due to gangrene infection, something Flavius reported with poorly concealed satisfaction. Soon afterward, some stereotypes from Greco-Egyptian culture would be picked up and ‘creatively’ expanded upon in the following centuries.

Attention all readers!

As content creators on Medium.com, we face minimal compensation for our hard work. If you find value in my articles, please consider supporting me on my “Buy Me a Coffee” page. Your small contributions can make a big difference in fueling my passion for creating quality content. Thank you for your support!