A conservative Evangelical icon was secretly a queer feminist

Elisabeth Elliot’s horror story is finally told

If you grew up Evangelical from the 1970s into the 2000s, she was the church leader who told you what God said about sex. It was pretty much just “No.”

She was the voice of tradition, of rules and punishments, and a household name in America’s largest religion. A new biography tells an amazing story. At the start of Being Elisabeth Elliot, Ellen Vaughn warns: “If you want the expected version of Elisabeth Elliot’s story, don’t read this book.”

But I still wasn’t prepared.

Elisabeth Elliot became famous by a fluke.

In 1953, Betty Howard, as she was originally called, married a missionary named Jim Elliot. In 1956, he was was slaughtered in the jungle of Ecuador.

Evangelicals became very interested in this ‘martyr’, and she published two books, Though Gates of Splendor and Shadow of the Almighty, presenting him as a saint. Each were received as classics of the faith.

She continued their work in Ecuador, then became disillusioned by the idea of “converting” Third World people. She returned to America in 1964, much in demand as a speaker—but her heart wasn’t in it.

She was struck by the “sheer phoniness” of Christians.

Where before she’d seen sweet devotion, she now saw “intellectual sterility” and “insufferable bigotry in the churches.”

She writes in her diary of one scene where a pastor was going on and on about not smoking cigarettes being the great test of faith. “I can no longer cope with this kind of mind,” she writes. “It is painful in the extreme…”

She tried attending a Baptist church and found it “pathetic” — just a lot of “platitudes” that now seemed dishonest.

In contrast, non-Christians seemed very different than she’d been raised to expect. As she puts it in one diary entry: “I am always impressed with the way people of ‘the world’ simply accept one another without criticism, with openness and warmth and human love.”

At age 38, the famous Christian had to totally re-evaluate what she believed.

There are startling scenes. She bought a copy of Playboy magazine, looking at the pictures and reading the articles. To find Elisabeth Elliot buying and reading a pornographic magazine is truly amazing.

But all her sexual ideas were in motion. She realized she was fine with female clerics. She got into ongoing battles with her Baptist mother. In her diary she writes:

“Mother has never allowed her children to be persons. They are mere projections of herself, and when they cease to project what she visualizes she feels threatened, she cannot cope.”

Her mother was concerned about a ‘mutual friend’ who was lesbian.

In a letter in reply, Elisabeth Elliot rejects the idea being lesbian was “sin,” and articulates a radically pro-queer Christianity. She explains:

“Sin only enters when the law of love is transgressed, if I understand Jesus’ interpretation of the law. David and Jonathan clearly had a much deeper love than the usual man-to-man friendship. They met in secret, they kissed one another, and they frankly said it passed the love of women. I’m not building a doctrine on this — I only want to face up honestly to what we are told in Scripture, not ignoring or explaining away any facet of it. Perhaps the truth is that there are no such things as lines drawn, coincident with sex. Love is a great thing.”

To find Elisabeth Elliot explaining that the Bible’s David and Jonathan were having a homosexual relationship — and saying it was divine with reference to the teachings of Jesus—is just surreal.

It seems to have been her deeply-felt belief. Her brother recalls her saying: “I’m not even sure if there are any absolutes in life—unless it be love. Maybe love is an absolute. But everything else is not an absolute.”

She moved to New Hampshire, and got a book contract to write about whatever she wanted.

But she found herself mostly catching up on the literary world she’d missed out on as a Christian. In Ecuador, she had read Katharine Mansfield, saying her thought processes were “wholly transformed.”

Now she read T.S. Eliot and Isak Dinesen, Hemingway and Flannery O’Connor. She loved the movie of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—trying to see it as “Christian” in its truthful ‘ugliness’.

She writes in her diary:

“I am astounded at my present ability to understand and appreciate things.”

She had dreams of being a writer for The New Yorker or other mainstream magazines. The ones who took her articles were Christian.

She decided to be a novelist — to secular readers.

She wrote a semi-autobiographical novel, No Graven Image, about a female missionary who became disillusioned. It was published in 1966 and horrified the Evangelical world.

She had fans. A Christian historian named Paul Woolley wrote her:

“The dream world in which so much Christianity lives has become a barrier that almost completely isolates it from the realities of present existence.”

There is queer subtext.

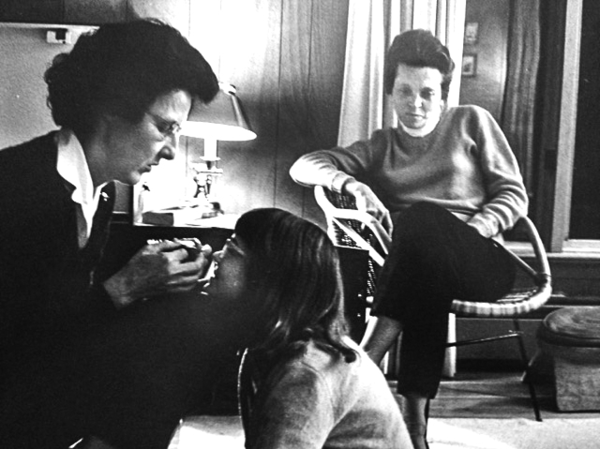

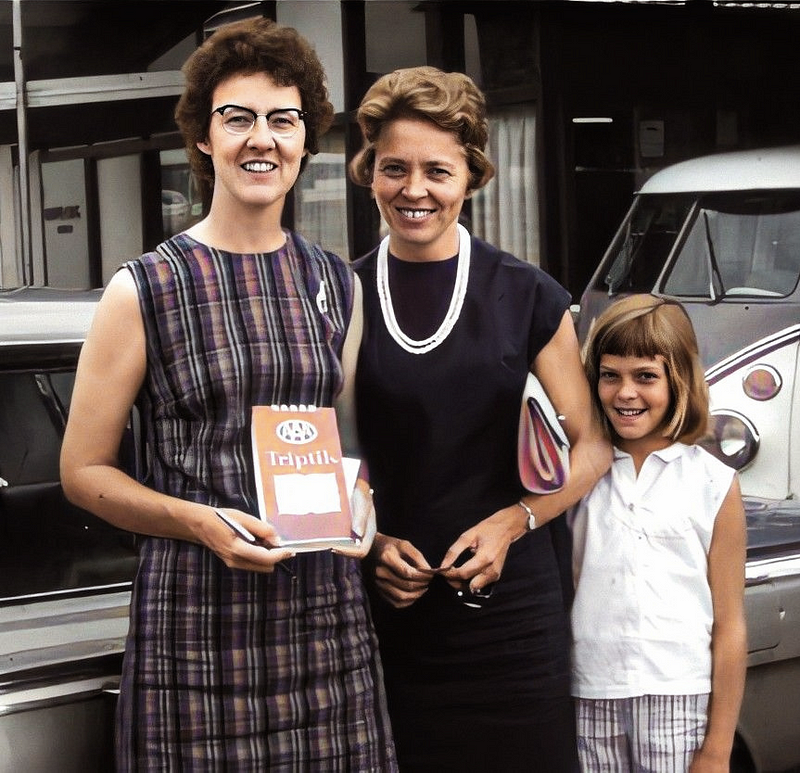

Ellen Vaughn tiptoes around a peculiar situation. Only far into the book, in chapter 5, does she mention that Elisabeth Elliot had left Ecuador in the company of “Van” or Eleanor Vandevort.

The two women had known each other for years, and would live together over the next decade.

She loved the great liberal writers of the day.

Elisabeth Elliot read and enthused over Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt, Susan Sontag. Her range of interests clearly suggest she’d come to see herself as liberal and feminist—and struggling to see her new interests as ‘Christian’.

Her desire to write in a similar ‘secular’ style was a war with herself, for it would mean leaving the Christian world. Elisabeth Elliot anguished in her diary: “Leave them? Without a voice or a vision?”

A key drama happened in 1967 when a Life celebrity interviewer, Dick Meryman, came to do a feature interview. Elisabeth Elliot fretted over what she would say. “Speak the truth and let the chips fall…?”

When she saw the transcripts, she couldn’t bear to have it published. What she’d said remains unknown.

As much as she disliked Christians, she was a Christian star.

She kept attending Christian events. “These men are conscious of power,” she writes after one. “Each has his road company, his show, his production.”

There were grim scenes when she’d speak, as Christian men stood up to lay into her as a non-Christian. She records one such speech:

“Do you know Christ as your Savior? Are you washed in the blood of the Lamb? No you are not. I want to tell you that you are totally LOST.”

A key incident happened in 1967 when she and Van visited Eugenia Price.

Arriving at a mansion in Georgia, they met the ultra-successful Christian writer turned romance novelist—and her female partner. Elisabeth Elliot seems to have been horrified when studying her host’s body:

“She sat with feet apart, elbows on knees, smoking a cigarette in a holder… She wears a pixie haircut, is overweight, and had on no makeup.”

That is to say, Eugenia Price was lesbian. Elisabeth Elliot left in disgust. Was it a glimpse of her own future with Van? That she couldn’t bear.

Not long after, a womanizing Christian theologian started to ‘womanize’ her.

She liked him as well. They made each other more famous. Marrying Addison Leitch, Elisabeth Elliot was ‘re-Christianized’ in the religion where marriage is the only real practice.

Her famous insistence that a Christian woman accept a husband’s “headship” takes on new suggestion. She wanted to stop struggling over what to believe. She’d believe what her husband believed — and sell it.

She launched into religious writings again, realizing there was a big job opening for an Evangelical woman speaking against feminism. In books like Let Me Be a Woman, she presented herself as the Evangelical champion of traditional ideas of gender.

After a deep depression, Van let go of the woman she’d imagined being with for the rest of her life.

The way she’d been dumped seems, at this point, cruel. But Elisabeth Elliot charged forward, telling herself that her second husband was her life’s great love story. Even Jim Elliot, she’d reflect, had been indifferent to her.

Then Addison got cancer and died, and she was more alone than ever.

She began taking boarders into her home.

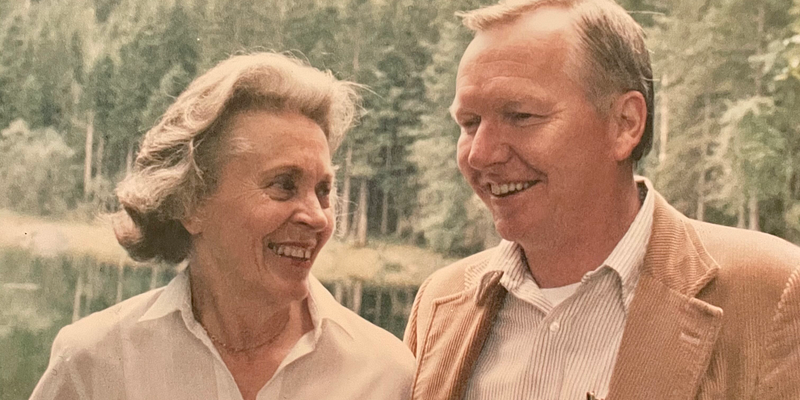

One of them was a man named Lars Gren. Originally from Norway, he’d mostly lived in the South and worked as a salesman of women’s clothes.

He became determined to marry her. Elisabeth Elliot was uninterested in him personally, but began to think the match advantageous. As Ellen Vaughn puts it, marrying a third husband was not an act of love, but “loneliness, deep need for affirmation, physical hunger, weariness, and desire to be ‘protected’…”

There would also be her career. A married Elisabeth Elliot was more marketable to the Evangelical world.

Lars Gren concealed his true self during their courtship.

He could seem “charming, funny, engaging,” but the night of their wedding he began to get nasty, as Elisabeth Elliot realized then she’d made a terrible mistake. Lars became a “cold, controlling, angry” man who daily took it all out on her. As Vaughn writes:

“Elisabeth found herself in a marriage characterized by control. Her husband dictated the thermostat setting, listened in on her conversations, interrupted her time with others, criticized her habits, and often pulled her away from people she enjoyed.”

It was, Vaughn writes, “a deal she must have struck within herself in which she gave up freedom for security.”

But Lars was a gifted manager of her career.

He took to micro-managing ‘Elisabeth Elliot’ down to scripting her gestures in public appearances. He knew what the religion wanted from her, and guided her into giving that performance. She became vastly more famous and respected in the Christian world.

If he didn’t like how she performed, he punished her, getting “purple with rage,” as she kept trying to appease him.

Any marriage problem, she liked to say, could be fixed by the woman “submitting.” As her husband was perpetually irritated or angry at her, she took her own advice, and tried to do whatever he said.

If her audience knew was going on between them, she wrote Lars, they would “find my words hard to swallow. And I nearly choke on them myself sometimes.”

But she kept putting on the show.

Ellen Vaughn has not even a mention of Elisabeth Elliot’s “purity” phase.

It’s a striking omission. A 1984 book, Passion and Purity, was a monster bestseller and set the course for Evangelical Christianity for two decades. Saying that dating was not necessary, that even holding hands was a sin, the book was the founding text of the religion’s “purity culture.”

A re-reading is now required. The book was foisted on millions of Evangelical teenagers as if coming directly from God. We see the book was not even Elisabeth Elliot’s views.

It was not a portrait of Jim Elliot, the special divine servant. It was more a portrait of her third husband, the one currently pulling her strings.

And Lars, it turned out, was not even Christian. Vaughn reports that he “gave his life to Jesus in 2019.”

He’d made her work even when she was succumbing to dementia.

Into the early 2000s, Elisabeth Elliot became a tragic spectacle of a woman who was unfit to work, but being made to do gigs. Vaughn reports:

“The family staged an intervention, removing Elisabeth, who had agreed, to an undisclosed location outside the United States. They pleaded with Lars. But over time, Elisabeth herself begged to go back to Lars. ‘He is my husband,’ she said. ‘He is my head.’”

Then she was mentally gone—leaving her own saintly reputation, but also confusion. In a 2014 profile, Lars recalls a young woman asking her: “Who’s the real Elisabeth Elliot?”

Elisabeth Elliot replied: “I don’t know, and may God keep me from ever finding out.” 🔶

Added: The Evangelical world anguishes over a very minimized discussion of this subject, focusing on EE’s ‘abusive’ third marriage.